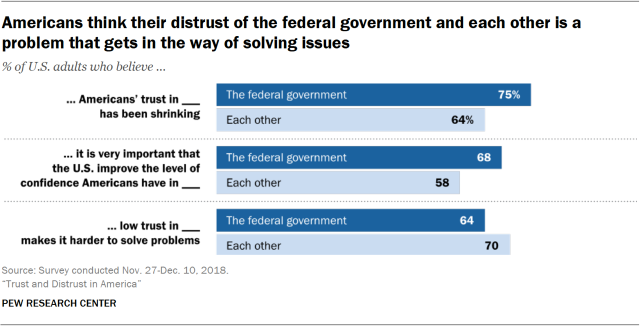

Trust is an essential elixir for public life and neighborly relations, and when Americans think about trust these days, they worry. Two-thirds of adults think other Americans have little or no confidence in the federal government. Majorities believe the public’s confidence in the U.S. government and in each other is shrinking, and most believe a shortage of trust in government and in other citizens makes it harder to solve some of the nation’s key problems.

As a result, many think it is necessary to clean up the trust environment: 68% say it is very important to repair the public’s level of confidence in the federal government, and 58% say the same about improving confidence in fellow Americans.

Moreover, some see fading trust as a sign of cultural sickness and national decline. Some also tie it to what they perceive to be increased loneliness and excessive individualism. About half of Americans (49%) link the decline in interpersonal trust to a belief that people are not as reliable as they used to be. Many ascribe shrinking trust to a political culture they believe is broken and spawns suspicion, even cynicism, about the ability of others to distinguish fact from fiction.

In a comment typical of the views expressed by many people of different political leanings, ages and educational backgrounds, one participant in a new Pew Research Center survey said: “Many people no longer think the federal government can actually be a force for good or change in their lives. This kind of apathy and disengagement will lead to an even worse and less representative government.” Another addressed the issue of fading interpersonal trust: “As a democracy founded on the principle of E Pluribus Unum, the fact that we are divided and can’t trust sound facts means we have lost our confidence in each other.”

Even as they express doleful views about the state of trust today, many Americans believe the situation can be turned around. Fully 84% believe the level of confidence Americans have in the federal government can be improved, and 86% think improvement is possible when it comes to the confidence Americans have in each other. Among the solutions they offer in their open-ended comments: muffle political partisanship and group-centered tribalism, refocus news coverage away from insult-ridden talk shows and sensationalist stories, stop giving so much attention to digital screens and spend more time with people, and practice empathy. Some believe their neighborhoods are a key place where interpersonal trust can be rebuilt if people work together on local projects, in turn radiating trust out to other sectors of the culture.

The new survey of 10,618 U.S. adults, conducted Nov. 27-Dec. 10, 2018, using the Center’s nationally representative American Trends Panel, covers a wide range of trust-related issues and adds context to debates about the state of trust and distrust in the nation. The margin of sampling error for the full sample is plus or minus 1.5 percentage points.

In addition to asking traditional questions about whether Americans have confidence in institutions and other human beings, the survey explores links between institutional trust and interpersonal trust and examines the degree to which the public thinks the nation is shackled by these issues. This research is part of the Center’s extensive and ongoing focus on issues tied to trust, facts and democracy and the interplay among them.

Here are some of the main findings.

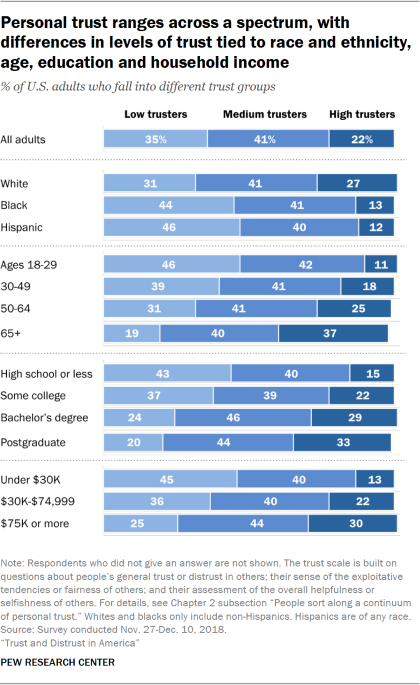

Levels of personal trust are associated with race and ethnicity, age, education and household income. To explore these connections, we asked questions about people’s general trust or distrust in others, their sense of the exploitative tendencies or fairness of others, and their assessment of the overall helpfulness or selfishness of others. Then, we built a scale of personal trust and distributed people along a spectrum from least trusting to most trusting. About a fifth of adults (22%) display consistently trustful attitudes on these questions, and roughly a third (35%) express consistently wary or distrustful views. Some 41% hold mixed views on core personal trust questions.1

There are some notable demographic variations in levels of personal trust, which, even in these new contexts, follow historic trends captured by the Center and other researchers. The share of whites who show high levels of trust (27%) is twice as high as the share of blacks (13%) and Hispanics (12%). The older a person is, the more likely they are to tilt toward more trustful answers. The more education Americans have, and the greater their household income, the greater the likelihood they are high on the personal trust spectrum. Those with less income and education are markedly more likely to be low trusters.

In other words, personal trust turns out to be like many other personal attributes and goods that are arrayed unequally in society, following the same overall pattern as home ownership and wealth, for example. Americans who might feel disadvantaged are less likely to express generalized trust in other people.

Strikingly, nearly half of young adults (46%) are in the low trust group – a significantly higher share than among older adults. Also, there are no noteworthy partisan differences in levels of personal trust: Republicans and Democrats distribute the same way across the scale.

It is worth noting, of course, that while social trust is seen as a virtue and a societal bonding agent, too much trust can be a serious liability. Indiscriminate trusters can be victimized in any number of ways, so wariness and doubt have their place in a well-functioning community.

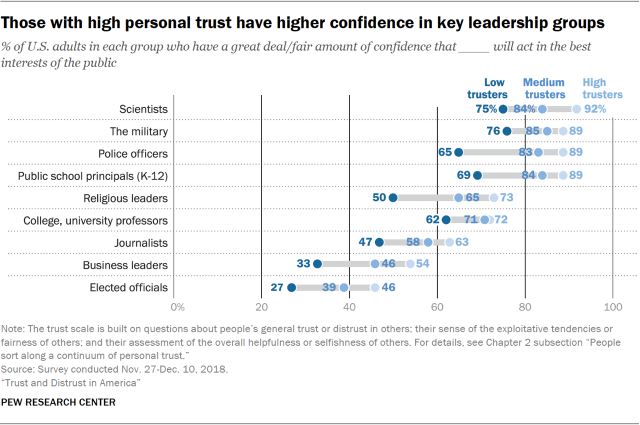

Levels of personal trust tend to be linked with people’s broader views on institutions and civic life. The disposition of U.S. adults to trust, or not to trust, each other is connected with their thinking about all manner of issues. For instance, those who are less trusting in the interpersonal sphere also tend to be less trusting of institutions, less sure their fellow citizens will act in ways that are good for civic life and less confident that trust levels can rise in the future.

Also, Americans’ views on interpersonal trust provide strong clues to how they think their fellow citizens will react in a variety of civic circumstances; their confidence in groups ranging from the military to scientists, college professors and religious leaders; and the strategies they embrace for dealing with others. For example, low trusters are much more likely than high trusters to say that skepticism is the best mindset for most situations (63% of low trusters say this vs. 33% of high trusters). They also are more likely than high trusters to say that being self-reliant is a better choice than working together with others (33% vs. 24%).

When Americans perceive that trust in the federal government has been shrinking, they are right. Long-running surveys show that public confidence in the government fell precipitously in the 1960s and ’70s, recovered somewhat in the ’80s and early 2000s, and is near historic lows today. Although there is a widespread perception that trust in other people also has plummeted, whether that truly has happened is not as clear, partly because surveys have asked questions about personal trust less frequently or consistently.

By and large, Americans think the current low level of trust in government is justified. Just one-in-four (24%) say the federal government deserves more public confidence than it gets, while 75% say that it does not deserve any more public confidence than it gets. Similarly, among U.S. adults who perceive that confidence in each other has dropped, many think there is good reason for it: More than twice as many say Americans have lost confidence in each other “because people are not as reliable as they used to be” (49% support that statement) than take the opposite view, saying Americans have lost confidence in each other “even though people are as reliable as they have always been” (21% say that).

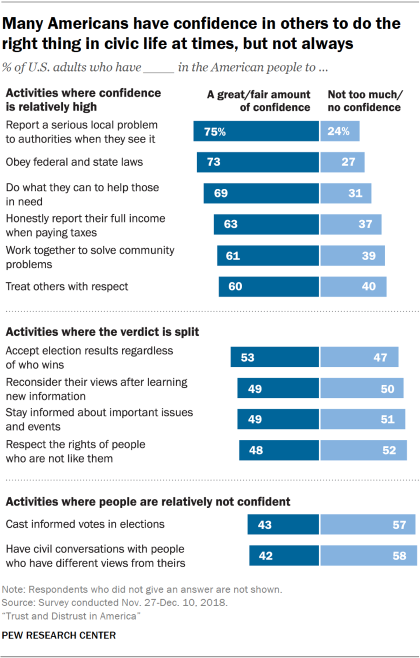

The trust landscape isn’t entirely bleak: Most Americans have confidence others will uphold key civic virtues, though not in every case. Clear majorities of Americans are confident their fellow citizens will act in a number of important pro-civic ways. This includes reporting serious local problems to authorities, obeying federal and state laws, doing what they can to help those in need and honestly reporting their income when paying taxes.

However, this level of confidence does not extend across all civic activities. It seems to plunge as soon as politics enter the picture. U.S. adults render a split verdict on whether they can count on fellow Americans to accept election results regardless of who wins: 53% express “a fair amount” or “a great deal” of confidence that others will accept the results, while 47% say they have “not too much” or “no confidence at all” that others will accept the election outcome. Americans also are split on whether they can rely on others to reconsider their views after learning new information (49% have at least some confidence, 50% little or none), stay informed about important issues and events (49% vs. 51%) and respect the rights of people who are not like them (48% vs. 52%).

Moreover, in some areas Americans do not expect others to act in civically helpful ways. Some 58% of adults are not confident that others can hold civil conversations with people who have different views, and 57% are not confident others will cast informed votes in elections.

One notable pro-trust finding is that, at least in principle, more adults embrace collaboration than individualism. Asked about the best way to navigate life, 71% say it is better in most situations for people to work together with others, compared with 29% who say it is better to be self-reliant.

Additionally, the inclination of Americans to express different levels of trust depending on the circumstances is reflected in their views on various institutions and kinds of leaders. The military enjoys “a great deal” or “fair amount” of confidence among 83% of U.S. adults, as do scientists (83%). Not far behind are principals of K-12 public schools (80%) and police officers (78%).2 Confidence in journalists stands at 55%.3

These supportive views stand in contrast to the public’s overall lack of confidence in elected officials and corporate leaders: 63% express little confidence in elected officials, and 56% take a similarly skeptical view of business leaders.

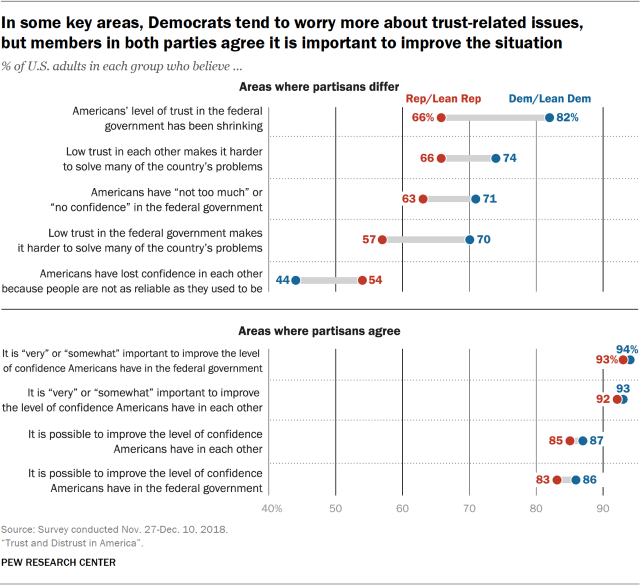

Democrats and Republicans think differently about trust, but both groups wish it would rise. Although supporters of the country’s two main political parties hold similar levels of personal trust, Democrats and those who lean Democratic are more likely than Republicans and Republican leaners to express worry about the state of trust in America. For example, Democratic partisans are more likely to say that trust in the federal government is shrinking (82% vs. 66%) and that low trust in the federal government makes it harder to solve many of the country’s problems (70% vs. 57%).

At the same time, there is bipartisan agreement that it is important to improve trust in both the federal government and in fellow Americans, as well as that there are ways to do so.

There are some partisan differences, too, when it comes to confidence in Americans to act in some civically beneficial ways. For instance, 76% of Republicans and 63% of Democrats (including independents who lean toward each party) have confidence people would do what they can to help those in need. Similarly, 56% of Republicans and 42% of Democrats have confidence the American people respect the rights of people who are not like them.

Partisan differences also show up in the levels of trust extended toward various kinds of leaders, including the military, religious leaders and business leaders (groups toward whom Republicans are more favorable than Democrats) as well as scientists, public school principals, college professors and journalists (groups that generally enjoy more confidence among Democrats than among Republicans).

There is a generation gap in levels of trust. Young adults are much more pessimistic than older adults about some trust issues. For example, young adults are about half as hopeful as their elders when they are asked how confident they are in the American people to respect the rights of those who are not like them: About one-third (35%) of those ages 18 to 29 are confident Americans have that respect, compared with two-thirds (67%) of those 65 and older.

There is also a gap when it comes to confidence that Americans will do what they can to help others in need. More than four-in-ten young adults (44%) are confident the American people will accept election results no matter who wins, compared with 66% of older adults who believe that’s the case.

At the same time, older Americans are more likely to believe Americans have lost confidence in each other because people are not as reliable as they used to be: 54% of those ages 65 and older take this position, compared with 44% of those 18 to 29.

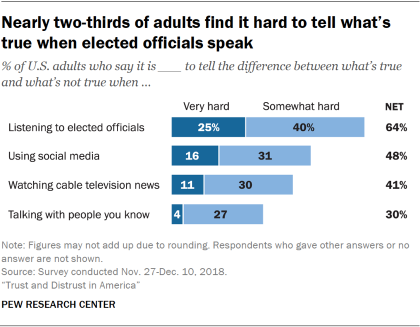

Majorities believe the federal government and news media withhold important and useful information. And notable numbers say they struggle to know what’s true or not when listening to elected officials. People’s confidence in key institutions is associated with their views about how those institutions handle important information. About two-thirds (69%) of Americans say the federal government intentionally withholds important information from the public that it could safely release, and about six-in-ten (61%) say the news media intentionally ignores stories that are important to the public. Those who hold these views that information is being withheld are more likely than others to have greater concerns about the state of trust.

Significant shares also assert they face challenges separating the truth from false information when they are listening to elected officials and using social media. Some 64% say it is hard to tell the difference between what is true and not true when they hear elected officials; 48% say the same thing about information they encounter on social media.

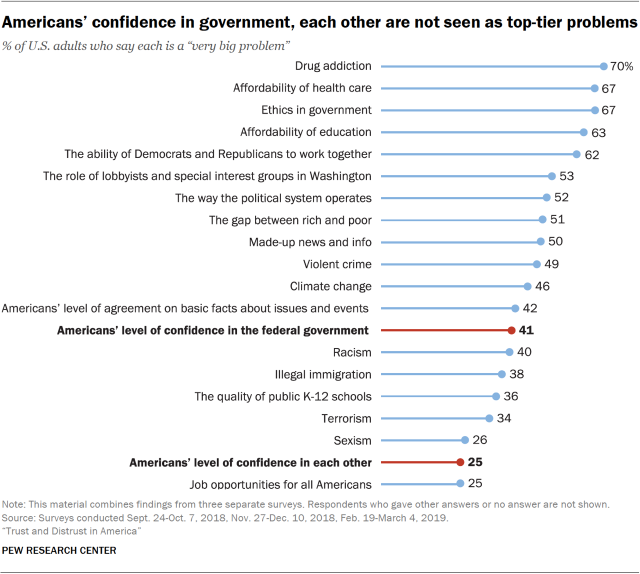

On a grand scale of national issues, trust-related issues are not near the top of the list of Americans’ concerns. But people link distrust to the major problems they see, such as concerns about ethics in government and the role of lobbyists and special interests. The Center has asked questions in multiple surveys about how Americans judge the severity of some key issues. This poll finds that 41% of adults think the public’s level of confidence in the federal government is a “very big problem,” putting it roughly on par with their assessment of the size of the problems caused by racism and illegal immigration – and above terrorism and sexism. Some 25% say Americans’ level of confidence in each other is a very big problem, which is low in comparison with a broad array of other issues that Americans perceive as major problems.

It is important to note, though, that some Americans see distrust as a factor inciting or amplifying other issues they consider crucial. For example, in their open-ended written answers to questions, numbers of Americans say they think there are direct connections between rising distrust and other trends they perceived as major problems, such as partisan paralysis in government, the outsize influence of lobbyists and moneyed interests, confusion arising from made-up news and information, declining ethics in government, the intractability of immigration and climate debates, rising health care costs and a widening gap between the rich and the poor.

Many of the answers in the open-ended written responses reflect judgments similar to this one from a 38-year-old man: “Trust is the glue that binds humans together. Without it, we cooperate with one another less, and variables in our overall quality of life are affected (e.g., health and life satisfaction).”

Americans offer a range of insights about what has happened to trust, the consequences of distrust and how to repair these problems. The open-ended survey questions invited respondents to write, in their own words, why they think trust in the U.S. government and in fellow Americans has eroded, what impact rising distrust has on government performance and personal relations, and whether there are ways trust might be restored. Some of the main findings:

Why trust in the federal government has deteriorated in the past generation: Some 76% of Americans believe trust in the federal government has declined in the past 20 years. When asked what happened, the respondents to this question offer a wide range of diagnoses, some of which are more commonly cited by Republicans, others of which are Democrat-dominated. Overall, 36% cite something related to how the U.S. government is performing – whether it is doing too much, too little, the wrong things or nothing at all – including how money has corrupted it, how corporations control it and general references to “the swamp.” President Donald Trump and his administration are cited in 14% of answers, and the performance of the news media comes up in 10% of responses. Additionally, 9% of these respondents say distrust in government arises from big social forces that have swept the culture, such as rising inequality and the spread of individualism. Others mention the intractability of problems like climate change or illegal immigration, as well as increasing polarization among the public and its leaders.

Republicans and those who lean Republican are more likely that Democrats and those who lean that way to mention government performance problems and corruption (31% vs. 24%). But Democrats are more likely to cite Trump’s performance as a contributor to problems related to trust in the federal government (24% vs. 3%).

“People are jaded in this day and age. Elected officials cannot be trusted. There is a huge divide between Democrats and Republicans. Social media allows people to air dirty laundry. People are not as friendly and neighborly as they were years ago. Society has drastically changed!” Woman, 46

Why Americans’ trust in each other has deteriorated in the past 20 years: Some 71% think that interpersonal trust has declined. Those who take this position were asked why, eliciting a laundry list of societal and political problems: 11% believe Americans on the whole have become more lazy, greedy and dishonest. Some 16% of respondents make a connection between what they think is poor government performance – especially gridlock in Washington – and the toll it has taken on their fellow citizens’ hearts. About one-in-ten of these respondents say they blame the news media and its focus on divisive and sensational coverage.

“Cultural shift away from close-knit communities. Viewing everything through hyperpartisan political lenses. Lost the art of compromise. Empathy as well as generally attempting to understand and to help each other are all at disturbingly low levels. People are quick to attack and to vilify others, even without clear proof, solely on the basis of accusations or along partisan lines.” Man, 44

What would improve the public’s level of confidence in the federal government: Some 84% of Americans believe it is possible to improve the level of confidence people have in the government. Their written responses urge various political reforms, starting with more disclosure of what the government is doing, as well as term limits and restrictions on the role of money in politics. Some 15% of those who answered this question point to a need for better political leadership, including greater honesty and cooperation among those in the political class. A small share believes confidence will rise when Trump is out of office. Additionally, some offer specific roadmaps for rebuilding trust, often starting with local community-based solutions that rise upward to regional and national levels.

“1. If members of each party would be less concerned about their power and the next election and more concerned with how they can serve their people. Term limits a possibility. 2. Rules about lobbyists/corporate money influencing politicians. 3. Importance of ethics laws and follow through for violators. 4. Promoting fact-based legislation. 5. Better relations among both parties and leaders; this is not a war.” Woman, 63

What would improve Americans’ level of confidence in each other: Fully 86% believe it is possible to improve interpersonal confidence across the nation, and a number of their answers focus on how local communities can be laboratories for trust-building to confront partisan tensions and overcome tribal divisions. One-in-ten make the case that better leaders could inspire greater trust between individuals. Some suggest that a different approach to news reporting – one that emphasizes the ways people cooperate to solve problems – would have a tonic effect.

“Get to know your local community. Take small steps towards improving daily life, even if it’s just a trash pick-up. If people feel engaged with their environment and with each other, and they can work together even in a small way, I think that builds a foundation for working together on more weighty issues.” Woman, 32

Why Americans’ low public confidence in each other and in the federal government is a “very big” problem: Some 25% think this, and the majority of those who explain their views cite their distress over broad social issues, including the shriveling trust neighbors have in each other, the toll political partisanship and tribalism take on interpersonal relations, a rise in selfishness, or a decline in civility and moral behavior. Some mention political leaders.

“Everything is impacted by the lack of trust – and the driver of the declining trust is the head of the federal government. Trust cannot be repaired without truth – which is in short supply.” Woman, 56

The issues that cannot be effectively addressed because Americans do not trust the federal government: Nearly two-thirds (64%) say that low trust in the federal government makes it harder to solve many of the country’s problems. About four-in-ten of those who then give follow-up answers (39%) cite social issues topped by issues in immigration and the border, health care and insurance, racism and race relations, or guns and gun violence. Some also cite environmental issues, tax and budget matters, or political processes like voting rights and gerrymandering.

“The *entire* general functioning of society. Trust in the federal government is low due to, in my opinion, unqualified people running it who are often dishonest. When you can’t trust elected and appointed officials, it impedes essentially everything in the government’s purview from working properly.” Man, 30