Most believe that Americans’ trust in their government and in each other can be improved. They propose an array of solutions to achieve these improvements, including increasing government transparency, improving community cooperation and performing individual acts of kindness. A share of the public thinks that more political compromise on national issues could restore trust both in the federal government and in interpersonal relationships. Some make the case that more media focus on positive stories, like acts of collaboration, might inspire greater trust.

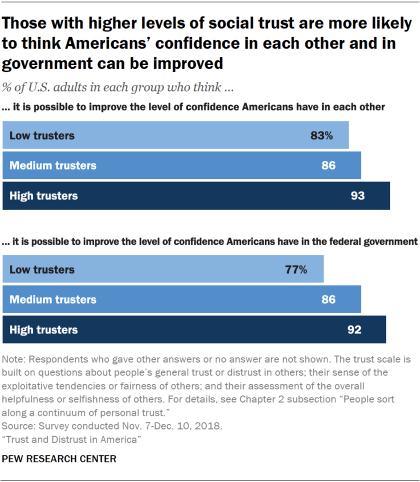

Overall, large majorities of Americans have hope that trust can be improved: 84% believe it is possible to improve the level of confidence Americans have in the federal government, and 86% believe it is possible to increase the confidence Americans have in each other. Substantial majorities across demographic groups and political persuasions embrace the idea that progress can be made, but some other variances among groups are worth noting. One consistent pattern is that those who are high on the personal trust scale are more likely than those who are low trusters to think that improvement is possible.

Although majorities of all demographic and political groups say it is possible to improve Americans’ confidence in the federal government, differences between groups still exist. For instance, whites (87%) are more likely than black (71%) or Hispanic adults (81%) to say that the level of confidence in the federal government can be improved. Those with college degrees or higher are more likely than those without a college degree to think things can be improved (91% vs. 81%, respectively). A similar gap exists between those living in households earning $75,000 or more and those in households earning less than $30,000 (91% vs. 77%). Patterns are similar when it comes to interpersonal trust.

Many think increasing government transparency and fixing leadership problems can increase confidence in the federal government

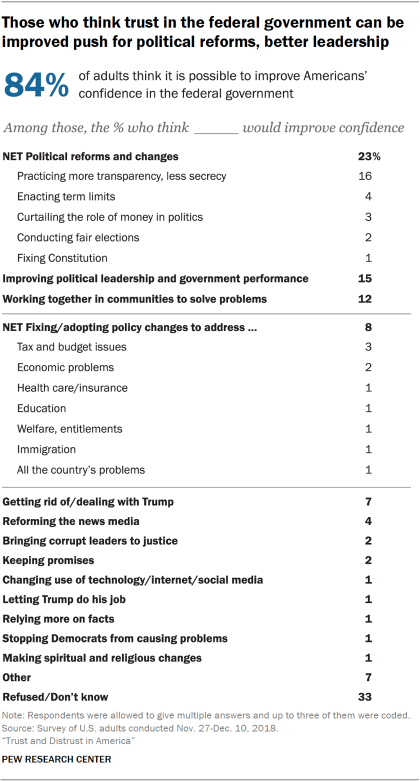

When they consider the past 20 years, those who are concerned about Americans’ declining confidence in the federal government cite a host of factors they think caused the decline, including polarization and gridlock, the overall poor performance of government, the role of money in politics, President Trump’s performance and behavior, and problems with media coverage of politics. Those who believe the situation can improve sketch out a variety of strategies for making things better.

About three-quarters (73%) of those who think it is possible to improve Americans’ confidence in the federal government offered an answer to the open-ended question we asked about solutions. About a quarter of them (23%) recommend political reforms, including less secrecy in government activities, more honesty from politicians, term limits and curtailing the role of money in politics. Another 15% call for general improvements in political leadership, while 7% specifically seek remedies to Trump’s behaviors and performance as a solution. Some 12% think collaborative problem solving that brings people together might prompt a better kind of national politics. An additional 8% cite policy fixes related to issues like taxing and spending, economic disparities and social safety net issues would increase confidence in the federal government.

In their written responses explaining how Americans’ confidence in government could be approved, many advocated for change in political culture and systems. One man, 49, advocated a wholesale makeover of political culture: “Our horrible, polarized, dysfunctional federal government is a result of an ignorant, naive, misinformed, polarized electorate addicted to social media and stupid entertainments. And it’s a result of gerrymandering, and the flawed electoral college system of electing a president. And of the overrepresentation of rural red states in the Senate. A good first step to improving confidence in the federal government would be to change the makeup of the government to better reflect the electorate.”

Others wrote that the quality of leadership has a direct effect on trust. A 69-year-old man wrote: “Elected officials with integrity would help immensely. I believe it is unethical to run for office based on criticism of your opponent. Sadly, people are elected based on who tells the best or most popular lies.”

Trump was prominently mentioned in a notable share of answers. At times, respondents like this woman, 51, argued that his departure from the scene would be helpful: “We are currently without a leader of any kind. Trump is the opposite of a leader, dividing and inflaming at every turn. He represents the death of democracy in America.”

Some argued the exact opposite and said allowing Trump to do his job would be a trust restorative. A 45-year-old woman put it this way: “President Trump’s agenda is constantly hitting roadblocks through the media’s biased coverage and the unnecessary investigations, a.k.a. the ‘witch hunt,’ to pave way for impeachment. Trump was elected based on his promises and he is doing an amazing job keeping his promises. A huge step to improve confidence in the federal government would be to let Trump do his job with accurate news coverage.”

A number of respondents pressed for reducing the role of money in politics because they think it distorts priorities in trust-harming ways. Said one man, 63: “We are not represented properly. Special interest groups and corporations run the government. Take money out of politics! If an elected official is sponsored by a special interest group, who is that official going to represent? It’s not complicated.” A similar fix-it approach came from this 52-year-old Gen X man: “Appoint people with ethics and the public at heart. Stop appointing people from industries they will oversee. Stop income inequality and stop trickle-down economics and tax breaks to the rich. Get more money into the middle class and to the poor. Stop making the rich richer and stop creating an oligarchy.”

Some respondents cited policy solutions they think would make people feel more confident about their government and its role in their lives. One wide-ranging answer came from a 68-year-old woman: “Guaranteeing affordable health care. Reining in election spending. Reining in corporate lobbying and campaign spending. Meeting obligations to veterans. Leading the Judiciary in sentencing reform and de-incarceration of matured, stable prisoners. Demilitarizing law enforcement. Reforming environmental regulation to be more equitable and less ponderous. Reforming agricultural protections to benefit smaller enterprises. Protecting the security of elections and electronic communication.”

Another woman took a different tack and argued that trust would increase if the federal government only focused on the matters it could effectively tackle. As she put it: “If we would face reality that the federal government … should not and is not able to solve all our problems. If it would focus on limited governing, and do that well, confidence could be improved.”

Some Americans argued that the tone and focus of the news media are at fault and that confidence in government would be restored with changes there. As a woman, 63, put it: “News media reports only the negative and sensationalizes it and ignores everything positive. If the public was given more positive information about things the government has done, confidence of the American people could be elevated.”

Others, like this 27-year-old man, made the case for compromise and greater reliance on expertise: “If our elected officials, including POTUS, made an actual effort to work together and compromise, that might improve trust. Additionally, if elected officials actually believed their country’s experts (e.g., scientists) and took heed of reports and recommendations, that may also improve confidence.”

A 52-year-old woman wrote about historic trends: “Confidence in the federal government has been eroding steadily over time. Watergate was the first blow to confidence in the federal government, then starting with Bill Clinton it has gone into a deep dive. People need to open their minds to others’ opinions rather than just holding onto what they already believe. The media and social media could do a better job of reporting the truth and setting the agenda, encouraging people to build bridges rather than creating continual division.”

Many Americans say interpersonal trust problems can be fixed with outreach efforts in their community and acts of kindness

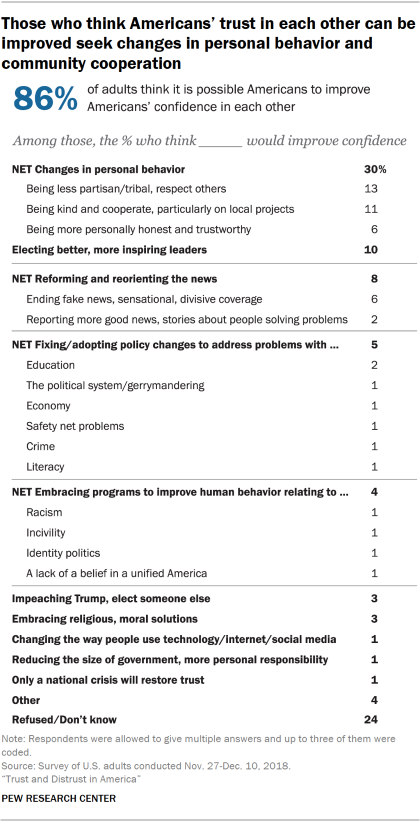

Some 72% of those who think it is possible to improve the level of confidence Americans have in each other answered an open-ended question seeking their ideas for solutions.

The most common recommendations among this group are for people to change their interpersonal behavior, with three-in-ten Americans (30%) offering proposals along those lines. These responses included suggestions that people be less tribal and partisan – that if people spent more time getting to know others, especially those whose views did not align with their own, they would end up finding interests or ideas in common. That, they argued, would increase trust.

One illustrative quote from open-ended answers in the survey came from a 66-year-old woman: “Each one of us must reach out to others. Even people who are the same, but unknown to you, an individual may distrust. It takes interaction with people face-to-face to realize that we do all inhabit this space and have a vested interest in working together to make it a successful, safe, and environmentally secure place to live. No man is an island.”

A related thought from a 47-year-old man: “Intentionally creating dialogue between differing sides: police with community members, principals with parents, politicians with each other, liberals and conservatives, different religious groups, etc. Skilled moderators probably will be necessary.”

Another group of respondents concentrates on the virtues of being kind and cooperating with others. Many of them believe that neighbors working side-by-side on local projects would inevitably lead to more trusting relationships in communities, and that such projects would draw people out of more isolated and lonely circumstances. One woman, 79, put it this way: “Seek common ground that engages as many as possible in the community and organize around a project that addresses that common concern.”

A third group of answers that fell in this category relate to individual accountability. These individuals argue that interpersonal trust would grow if people took responsibility for their lives and modeled trustworthy behavior for others. An illustrative quote from open-ended answers in the survey came from a 34-year-old woman, who said trust would improve if the country had “more people displaying more effort to take care of themselves, their health, their finances, their life-altering choices. Someone who can’t take care of themselves can’t be assumed to be able to take care of anything outside of themselves.”

Another 32-year-old woman said, “Get to know your local community. Take small steps towards improving daily life, even if it’s just a trash pickup. If people feel engaged with their environment and with each other, and they can work together even in a small way, I think that builds a foundation for working together on more weighty issues.”

One-in-ten (10%) who think interpersonal trust can be improved look at the role leaders play in setting the tone for the culture. They assert that better, more inspiring and less divisive leaders would set a tone for the country that would affect the way Americans think about the trustworthiness of others. For example, one 58-year-old man argued: “It starts with our leaders including: federal government, local governments, schools, businesses, etc. They must set examples for the people, showing honesty, integrity, and welfare for others and being less selfish. This would have a trickle-down effect on the whole. Until this happens, don’t plan on it getting any better.”

Some 8% seek improvements in media culture as the pathway to better person-to-person relationships. They attack things like “fake news,” biased coverage, one-sided story-telling and the way journalists focus on negative, divisive and sensational narrative lines. As one participant, a 42-year-old man, put it: “I believe that the media stokes much of the discord in public today. I think that sensationalism and opinion should be reduced and replaced by unbiased journalism as often as possible.”

A portion of respondents (2%) make the case that more good news about successes and feats of collaboration would show a side of community life that could ease interpersonal tensions and help people see that the world is not relentlessly foul. Here is how one 48-year-old man sees it: “News and media show all the negative/bad things going on, so people are not trusting of anyone. Media should show more of the good news and the good people do, rather than always reporting the bad things.”

A few Americans believe that Trump and his allies have made it harder to trust others; fewer make that argument about Democrats, but that did come up in fewer than 1% of the answers.

Others believe that improvements in policy areas or education spaces might ease interpersonal distrust. A portion of Americans also see a cause-effect connection between digital technology and social pathologies. They think that the degree to which people, especially younger Americans, spend time with their screens means they have withdrawn from interacting with others and that personal trust takes a hit. “I think society needs to not be glued to electronics and social media,” wrote a 51-year-old woman. “This affects people’s social skills and it often keeps them from dealing with reality.”