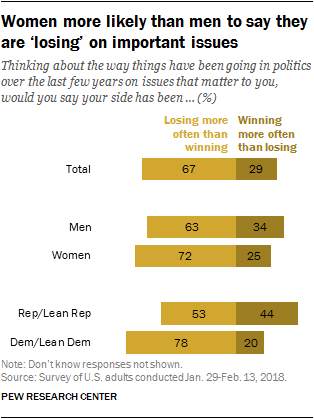

Two-thirds of Americans (67%) now say that, when it comes to “the way things have been going in politics over the last few years on issues that matter” to them, their side has been losing more often than it has been winning. Just 29% feel they have generally been winning more often than losing on the issues that matter to them in politics.

The share of Americans who say they are losing more than winning has increased 8 percentage points since 2016 (from 59% to 67% today).

Women are now more likely than men to say that, on balance, they are losing (72% vs. 63%); in early 2016, slightly more men (62%) than women (57%) felt like their political side was losing.

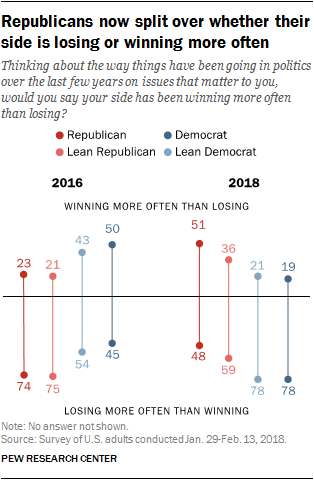

Partisans’ views also have shifted since before the 2016 election: 78% of Democrats and Democratic leaners now say they are losing more often than winning, up from 49% two years ago. Today, Republicans and Republican leaners are about evenly split (53% say losing more often, 44% say winning). In 2016, 75% of Republicans said they felt they were losing on the issues that mattered to them.

In the current survey, those who identify with the GOP are more likely than those who lean toward the Republican Party to say their side has been winning more often than losing (51% vs. 36%). Two years ago, there were no significant differences in these views.

Among Democrats, equally large majorities of those who identify with the party and those who lean Democratic (78% each) say they are losing more often than winning in politics. In 2016, more Democratic identifiers (50%) than leaners (43%) said their side was winning more often.

Perceptions of the public’s political wisdom and ability

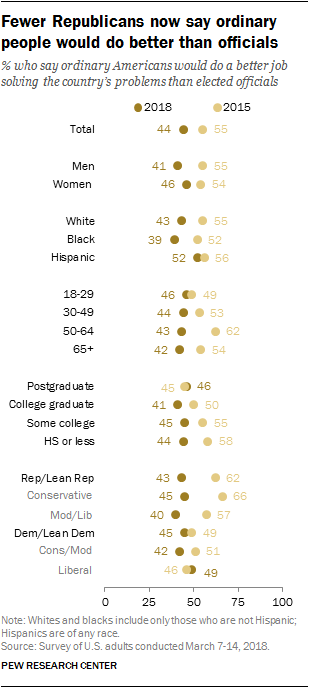

About half of the public (51%) says that ordinary Americans would not do a better job solving the country’s problems than elected officials, compared with slightly fewer (44%) who think they would do a better job. This marks a shift from 2015, when most (55%) said they thought ordinary Americans would do better than elected officials and just 39% said they could not do better.

This shift in views has been especially pronounced among Republicans and Republican leaners. Today, 43% of Republicans think ordinary Americans would do a better job than elected officials, down sharply from 62% who said this in 2015, during Barack Obama’s administration.

There has been little change in views among Democrats and Democratic leaners on this question: About as many are skeptical that ordinary Americans would do better than elected officials today (45%) as said this in 2015 (49%).

Older adults and those without a college degree have also become more skeptical about the public’s ability to do better than elected officials.

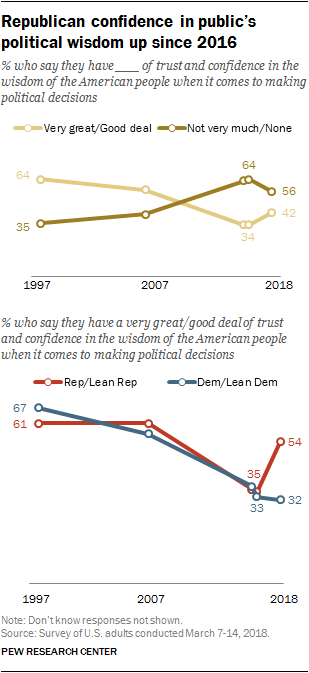

The public has become less confident in the ability of ordinary Americans to outperform elected officials, but they have become somewhat more positive when it comes to assessments of the political wisdom of the American people.

Today, 56% say that they have not very much or no confidence at all in the wisdom of the American people when it comes to making political decisions; 42% say they have a very great deal or good deal of confidence. While opinion is negative on balance, it is more positive than it was two years ago: In 2016, nearly two-thirds (64%) said they had not very much or no confidence in the public’s political wisdom.

Republicans and Republican leaners have driven this shift in overall views. In the current survey, 54% say they have a very great or good deal of confidence in the wisdom of the American people when it comes to making political decisions. In the spring of 2016, just 35% said this. By contrast, views among Democrats and Democratic leaners have not changed over the last two years: Just 33% expressed confidence in the public’s political wisdom in 2016 and about the same percentage says this today (32%).

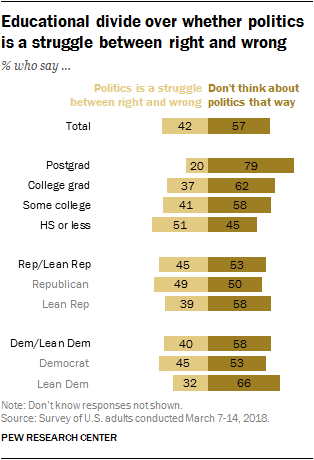

Majority of public says politics is not a struggle between right and wrong

Overall, 42% of Americans say they think about politics as a struggle between right and wrong, while a majority (57%) doesn’t think of politics in that way.

Just 20% of those with a postgraduate degree say they think about politics as a struggle between right and wrong, while 79% say they do not. Narrower majorities of those with bachelor’s degrees (62%) and those with some college experience (58%) also say they generally do not think about politics in these terms. In comparison, those with a high school education or less are divided: 51% say they think about politics in these terms, 45% say they do not.

Republicans and Democrats are about equally likely to say they see politics as a struggle between right and wrong. But partisan identifiers in both coalitions differ from those who say they lean toward (but do not identify with) the party. For instance, while 45% of Democratic identifiers say they think about politics as a struggle between right and wrong, just 32% of Democratic leaners say the same.

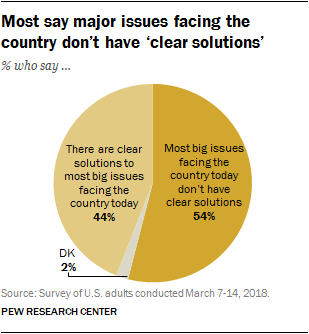

How clear are the solutions to the country’s issues?

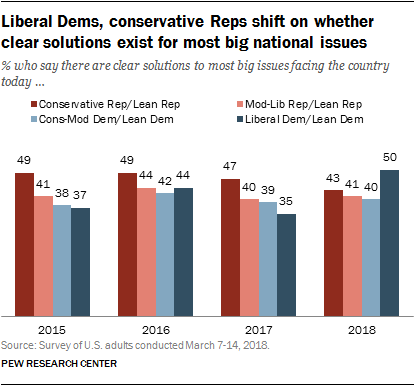

Just over half of Americans see the major issues facing the country today as complicated: 54% say that most big issues don’t have clear solutions, while 44% say the solutions are clear. This sentiment is little changed in the overall public over the past few years, but there have been shifts in how both conservative Republicans and liberal Democrats view the country’s problems.

In years past, conservative Republicans and Republican leaners were more likely than either Democrats or moderates and liberals in the GOP coalition to say that there were clear solutions to most of the big issues facing the country. Today, liberal Democrats and Democratic leaners are somewhat more likely than those in other groups to say solutions are clear.

Last year, 47% of conservative Republicans and 35% of liberal Democrats said solutions to most of the country’s big problems were clear.

Today, half (50%) of liberal Democrats say this, compared with 43% of conservative Republicans. Within both parties, views among the less ideological wings of the parties have not shifted over the last three years.

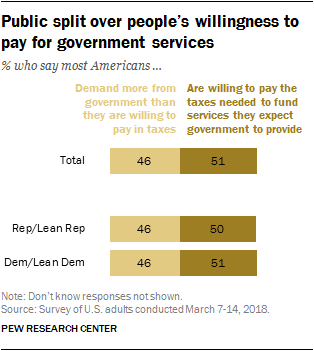

Americans are currently about evenly divided on the question of whether the public is willing to pay the taxes needed to provide the government services they expect (51%) or whether the public demands more from the government than they are willing to pay (46%). In 2015, Americans were slightly more likely to say the public usually demands more than it is willing to pay for (52%) than to say it was willing to pay for expected services.

As was the case in 2015, there is no partisan gap on this question. There also are no significant differences in these views across demographic groups today; this represents a change from 2015, when younger, more educated and higher-income people were more likely than others to say the public demanded more than it was willing to pay taxes for.

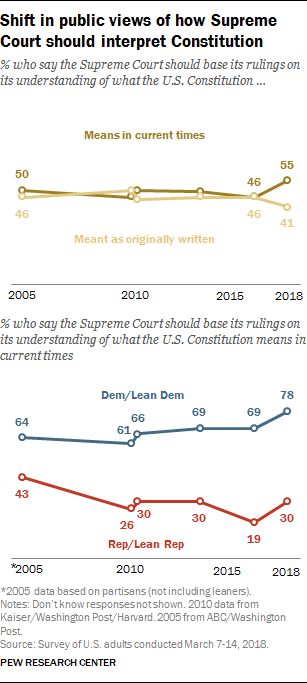

More say constitutional interpretation should address current meaning

A 55% majority of the public now says the U.S. Supreme Court should make its rulings based on what the Constitution “means in current times,” while 41% say the court should base its rulings on what the Constitution “meant as originally written.”

This reflects a shift in public opinion: In surveys dating back more than a decade (from 2005 to 2016), the public was roughly evenly divided in its views of how the Supreme Court should interpret the Constitution. When the question was last asked in October 2016, 46% said that the court should base its rulings on what the Constitution means in current times; the same share (46%) said rulings should be based on what the Constitution meant when it was originally written.

Nearly eight-in-ten Democrats and Democratic leaners (78%) now say rulings should be based on the Constitution’s current meaning, higher than at any previous point and up 9 percentage points from 2016. Just three-in-ten Republicans (30%) currently say the same; this reflects an 11-point increase from the fall of 2016, but is little different from GOP views in 2010 and 2011.

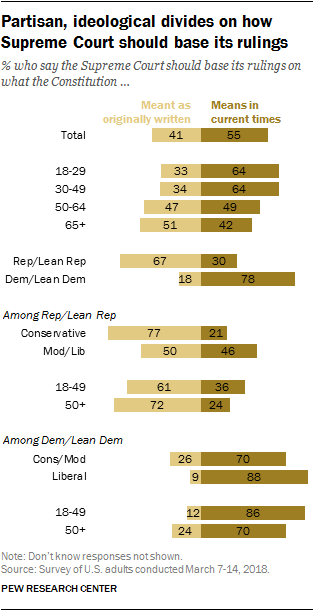

Conservative Republicans continue to overwhelmingly say the Constitution should be interpreted based on its original meaning (77%) rather than its meaning in current times (21%). But moderate and liberal Republicans and Republican leaners are more divided in their views: 50% say original meaning, 46% current times. There is a more modest ideological gap among Democrats, though liberal Democrats are more likely than conservatives and moderates to think the court should base its rulings on current meaning (88% vs. 70%).

There is a substantial age gap in these views: More than six-in-ten Americans younger than 50 (64%) say the high court should take current context into account when interpreting the Constitution. By comparison, only about half of those 50 and older (47%) say the same.

Although majorities of Republicans in all age groups say the Constitution should be interpreted as it was originally written, younger Republicans are somewhat less likely than older Republicans to hold this view (61% of Republicans ages 18 to 49 compared with 72% of those 50 and older).

Similarly, while wide majorities of Democrats of all ages say the Supreme Court should base its rulings on its view of the Constitution’s current meaning, older Democrats (70% of those 50 and older) are less likely than younger Democrats (86% of those 18 to 49) to say this.