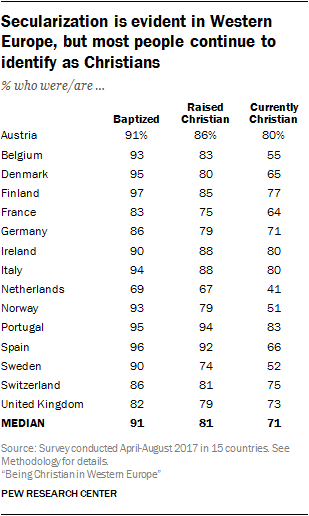

Most people in Western Europe identify as Christians. But across the region, fewer people say they are currently Christian than say they were baptized or raised as Christians.

In every country, net losses for Christians are accompanied by net gains for the share of adults who say they have no religion. College-educated people, younger adults and men are more likely than others to say they are now religiously unaffiliated after having been raised Christian.

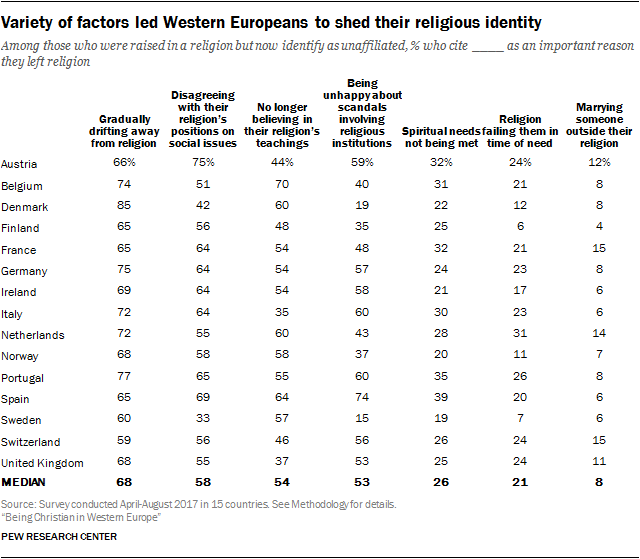

Those who were raised in a religion and now identify as unaffiliated cite several factors as important in their decision to leave their faith. Most say they “gradually drifted away from religion.” Majorities also report disagreeing with religious positions on social issues, like homosexuality and abortion, as a reason they no longer identify with a religion. And at least half of respondents in several countries, especially in predominantly Catholic ones, cite church scandals.

Most Western Europeans identify as Christian

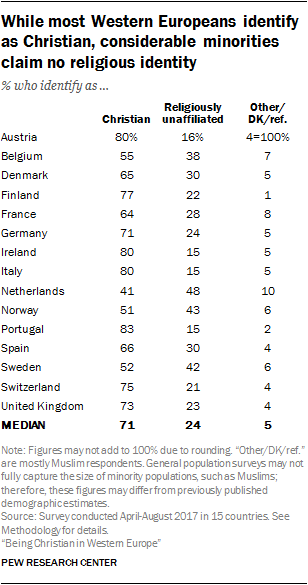

Across the countries surveyed, most adults identify as Christian, including eight-in-ten or more in Portugal (83%), Austria (80%), Ireland (80%) and Italy (80%). By contrast, the Netherlands has the lowest share of Christians in the region (41%).

Religiously unaffiliated adults — that is, those who do not identify with a religion, but describe themselves instead as “nothing in particular,” agnostic or atheist – are a sizable population in the region. Still, of the countries surveyed, only in the Netherlands do religiously unaffiliated adults outnumber Christians (48% vs. 41%).

Five hundred years after the start of the Protestant Reformation, most countries in the region are still either predominantly Catholic or predominantly Protestant. Generally, the Protestant countries have higher shares of unaffiliated adults than do Catholic countries in the region. For example, in Ireland, Italy and Portugal (all predominantly Catholic), just 15% of adults are religiously unaffiliated, compared with 23% in the UK and 30% in Denmark (both predominantly Protestant).

Younger adults (those between the ages of 18 and 34), men and college graduates are more likely to self-identify as religiously unaffiliated, while older respondents (age 35 and up), women and those with less than a college education are more likely to identify as Christian.

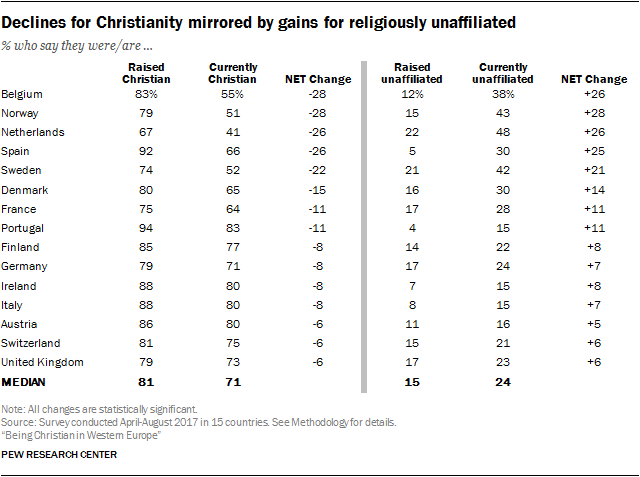

Decline in share of Christians is accompanied by gains for religiously unaffiliated

Even though majorities across the region identify as Christian, in every country surveyed, Christianity has experienced net losses as a result of religious switching. The vast majority of Western European adults say they were raised Christian, but significantly fewer in every country currently identify as Christian. The decreases in Christian identity are mirrored by increases in the shares who report having no religion.

Christians have seen the most substantial net losses in Belgium, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain and Sweden. For example, there is a difference of 28 percentage points between the share of Norwegians who were raised Christian (79%) and the share who are currently Christian (51%), matching the 28-point gap between those who were raised unaffiliated (15%) and the current unaffiliated share (43%).

In several countries, the share of religiously unaffiliated adults has more than doubled within the lifetime of the survey respondents. For instance, in Belgium, 12% of adults were raised unaffiliated and 38% report having no religion today. By comparison, the rise in the share of religiously unaffiliated adults has been more modest in Austria, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

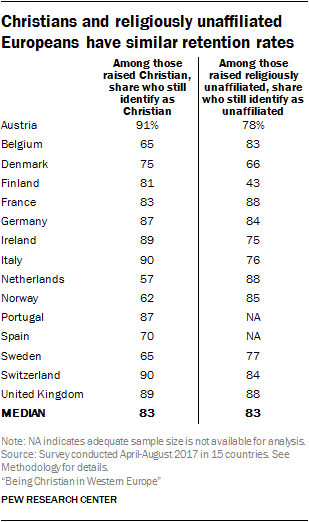

Overall, large majorities of those raised Christian still identify as Christian today, but Christians have relatively low retention rates (the share of all people raised as Christian who are still Christian) in Belgium (65%), Sweden (65%), Norway (62%) and the Netherlands (57%). The overwhelming majority of those who have left Christianity now identify as religiously unaffiliated.

Similarly, the vast majority of those raised religiously unaffiliated stay religiously unaffiliated, but significant minorities in some countries now identify as Christian or with some other religion, or give an ambiguous response about their current religion. In France, for example, 88% of those raised religiously unaffiliated are still religiously unaffiliated today, while 8% say they are now Christian and 4% say they now identify with another religion or do not provide a definitive response about their current religion.

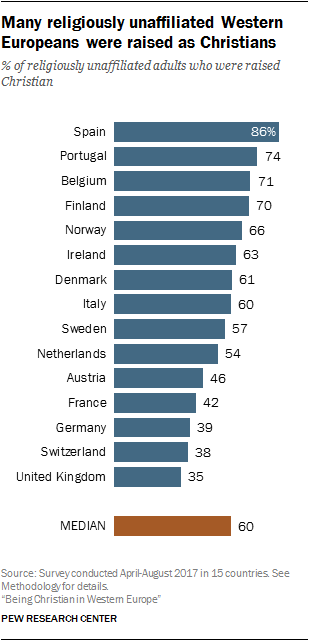

Among those who are currently unaffiliated, majorities in most Western European countries say they were raised as Christians. For example, 86% of current “nones” in Spain are former Christians, as are seven-in-ten or more in Portugal (74%), Belgium (71%) and Finland (70%).

Former Christians who are now religiously unaffiliated are significantly younger and more highly educated than current Christians. For example, in Switzerland, adults who have left Christianity are considerably more likely to be younger than 35 (52% among former Christians vs. 19% among current Christians) and to have a college education (57% vs. 37%).

Large shares of Western Europeans –including many unaffiliated adults – report having been baptized

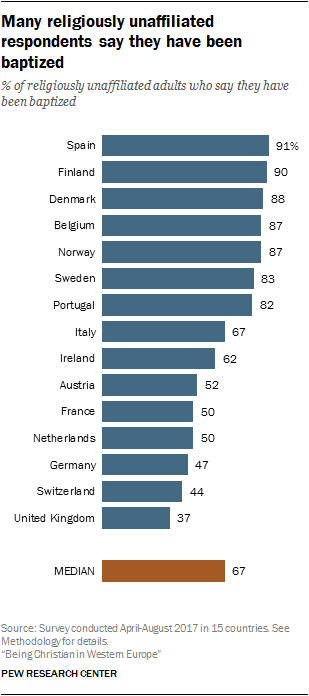

Generally, the share of people who say they were baptized is higher than the share of people who say they were raised as Christians. Across the region, the vast majority of adults (median of 91%) report having been baptized, including nearly all Christians in several countries.

Even among religiously unaffiliated adults in the region, half or more in most places report having been baptized, including roughly nine-in-ten in Spain (91%), Finland (90%) and Denmark (88%).

Why did unaffiliated people turn away from religion?

The survey asked people who were raised in a religion but are now unaffiliated whether each of seven possible factors was an important reason for the change. Respondents could choose as many reasons as apply. The most common reason, cited by majorities across the region, is that they “gradually drifted away from religion.” In addition, roughly half or more in most countries say they stopped believing in the teachings of their childhood religion, or that they disagreed with their religion’s positions on social issues like homosexuality and abortion.

Large shares (regional median of 53%) also cite scandals involving religious institutions and leaders as an important reason they no longer identify with a religion. This position is especially common in Catholic-majority countries such as Spain (74%), Italy (60%) and Portugal (60%).

Smaller shares say that they stopped identifying with a religion because their spiritual needs were not being met (median of 26%), or that religion failed them when they were in need (median of 21%). Even fewer say marrying someone who did not share their childhood faith (median of 8%) was an important reason for shedding their religious identity.

Sidebar: Europeans’ relationships with religion change over time

Focus groups in five countries explored how individuals’ religious identities, beliefs and practices have changed throughout their lives. Groups composed entirely of Christians or entirely of religiously unaffiliated adults shared stories about the role of religion during their childhoods. Many focus group participants considered themselves active Christians when they were young; they attended church regularly, prayed and held traditional religious beliefs. Several people in the groups said that when they reached their teenage and young adult years, they reduced their religious activity. Some turned completely away from organized religion. Focus group participants offered different explanations for how and why this shift occurred. A few participants pointed to particular moments when they lost faith and abandoned Christianity. Others said the attachment to Christianity faded gradually as they got older, with no particular turning point. Some mentioned specific disagreements with Christian teachings or disillusionments with church leaders and institutions, including recent scandals.

“My mum is Christian and her family are very sort of Protestant. My dad’s an atheist, so mum had more influence on the childhood. So we grew up relatively Christian just going to church at Easter, Christmas, that kind of thing. … When I was probably like 10, 11, it was just the kind of thing where I was in between atheism and Christianity. But my mum got cancer when I was about 12, and then I sort of like, on my own, just became quite religious. I had three sisters and none of them did it or anything. Dad was still an atheist; my mum didn’t really change her opinions. But I became sort of quite like praying all the time. I listened to a lot of country music, which I found really comforting so they would talk about God and stuff in it, and it was kind of like my turn towards religion in the struggle. And then, because she was cured a couple of years later, I was like, ‘Oh my God, it worked, God’s there for me.’ But then it was my interest in politics and stuff, and my exposure to lots of the more negative sides of Christianity in terms of social anachronistic ideas and stuff – so like opinions about gay marriage, or opinions about like sex before marriage and stuff. So when I was about 16, 17, I sort of thought, ‘Actually, I’m not too sure I agree with this institution.’… Now I’d probably say I’m agnostic.” – 20-year-old agnostic woman, United Kingdom

“We mostly celebrated Christmas. We didn’t really celebrate Easter or anything. No one in my family was religious in that way. No one talked about it. But in school there were the church’s children hours, and I went to those when I was younger … and the children’s choir in church. I started toward getting confirmed. But I stopped that because I didn’t think it was my thing when I got there – those meetings they had once a week. It felt a lot like they were imposing a lot on us about how to believe and about God, but I felt that I don’t believe this. I couldn’t stand and say something, or pray and write to God. For me it was really ‘No thank you,’ so I backed away and that’s the first time I realized – that’s when I felt that I don’t believe this.” – 26-year-old atheist woman, Sweden

[for church]

“Maybe halfway through primary school I started questioning it. And when the first death occurred in my family, I said ‘No, that is not it, this is not how it works.’ And then I was done with the whole thing.” – 29-year-old “nothing in particular” woman, Germany

“My parents are Protestant. When I was a kid, my mum used to take us with her to church. She tried to instill things in me about that. But I never got hooked. I never really followed. I went because she wanted me to go. In the end, I tried to avoid it – to avoid it totally. She tried to get me in it, but I refused to stay in it and follow everything that went with it because I wasn’t attracted by it. Later, we had a death in the family, which led me to be offended by faith. So, I ended up feeling hatred because of it. When we were younger, we used to have times of prayer in the family. But it didn’t continue. It all stopped. My parents, yes, they are really involved in it. But my sisters and I don’t talk about it at all. We each have our own beliefs, our own ritual … each one individually.” – 36-year-old Christian man, France

Focus group participants commonly described their early interactions with Christianity in terms of going to church, praying and being brought up with particular religious beliefs and identities, (e.g., Catholic, Lutheran, Church of England). Many practiced along with their families. Some described religious aspects of their youth as something that was imposed on them, calling them a “chore,” “tradition” or “obligation.” However, some in the focus groups said they have embraced these practices in adulthood; they now attend church services, pray occasionally or hold some religious beliefs. They gave a variety of reasons for these changes, such as wanting to teach Christian values to their children. Others started attending church to be part of a community or sing in a choir. Some participants say they have resumed aspects of Christianity, like praying on a regular basis, without adopting other traditional beliefs and practices.

While many of those who have left Christianity say they drifted away gradually, those who have returned to Christianity almost invariably pointed to a particular event, person or other circumstance that prompted them to come back to their childhood religion. And although participants talked about inconsistencies or contradictions in their religious practices – such as praying to God without believing there is a God – the group discussions typically revolved around an implicit assumption that Christians are supposed to attend church services, pray, believe in God, and mark key life passages (births, weddings, deaths) with religious ceremonies. Even as they talked freely about breaking these expectations – by seldom going to church, for example – the focus groups continually returned to the implicit paradigm, with each participant discussing the ways in which he or she adheres to or departs from it.

[pray]

“One day I was smoking some weed … and this band came over … and I was 16. And my friends were talking to them and I was like, ‘Oh, I’m going to talk to them.’ And then they started talking about God and stuff and I just sat at the back and listened and then they invited us to this gig night where you didn’t need any ID. So we brought along our bottles of White Lightning and then my friend who was really rebellious, way more rebellious than me, said she was going back to church and it was just in my head. And things kept popping up and kept popping up, and I was like 17 so I was really shy and really scared. And I made this pact: I was like, ‘OK if this and this happens, I’ll go back, I’ll go there.’ I’d never been, really. And then those things happened so I was like, ‘OK, I’m going to go.’ And I just quite liked the singing so I went back again. And then some people were like, ‘Oh, hi! We saw you…’ and started texting me, and I just kept going.” – 29-year-old Christian woman, United Kingdom

[for God]

“My parents did not have much to do with church, and I came to sing in a choir through a friend and learned how to play a few musical instruments and attended church every now and then. But since we never talked about it at home, I just experienced this with my friend a little bit – like how they did mealtime prayers and when we had sleepovers there, they prayed before bedtime. I missed that a little bit at home, but it just wasn’t a part of life there and as far as I was concerned that was OK. I realized when I had children and also through school and nurseries, that something is missing. And I started reading the Children’s Bible to my kids, but not in such a way as to force it on them, but to see how they would react to it and if they would wish for more, and that is what actually happened. By my children’s request – two boys – we attended children’s services regularly every week. One of them was absolutely thrilled. The other one went, ‘Well, let’s see’ – and that was it. And both of them have been christened, confirmed and the older one actually just got married in a church. And that was important to me – for them, because it was something I had missed, something I only experienced through a friend, and so it was important to me for the kids.” – 53-year-old Christian woman, Germany

[in God]

For details on the focus groups, including locations and composition, see Methodology.

Religious identity in the family

The survey asked respondents about the religion of their spouse or partner. The overwhelming majority of Christian adults who are married or living with a partner have a Christian spouse or partner (median of 94%), and most unaffiliated adults who are in such a relationship have an unaffiliated partner (65%).

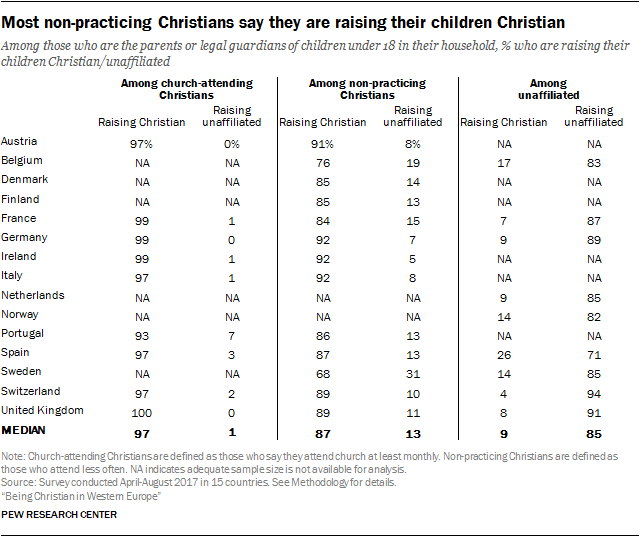

In addition, respondents who are the parents or legal guardians of children under 18 in their household were asked how they are raising their child or children with regard to religion. Large majorities of Christian parents, both church-attending and non-practicing, say they are raising their children Christian, although nearly a third (31%) of non-practicing Christian parents in Sweden and 19% in Belgium say they are raising their children with no religion.13

Religiously unaffiliated parents, meanwhile, are mostly raising their children without a religion, although 26% of unaffiliated parents in Spain say they are raising their children Christian.