Though the public is unhappy with government generally, Americans are largely divided on key measures of their ability to influence how it runs, including the impact of voting on government and the ability of motivated individuals to influence the way government works.

When asked which statement comes closer to their own views, most Americans (58%) say that “voting gives people like me some say about how government runs things,” while fewer (39%) say “voting by people like me doesn’t really affect how government runs things.”

The public is somewhat more skeptical when it comes to the ability of ordinary citizens to influence the government in Washington. Half (50%) say ordinary citizens can do a lot to influence the government in Washington, if they are willing to make the effort, while about as many (47%) say there’s not much ordinary citizens can do to influence the government.

Can ordinary people have an impact?

Majorities of Democrats and Democratic leaners as well as of Republicans and Republican leaners say that voting gives people some say in government, though this view is somewhat more widely held among Democrats (63%) than Republicans (56%).

Democrats are similarly more likely than Republicans to say ordinary citizens can influence the government in Washington: 55% of Democrats say ordinary citizens can make an impact, while 42% say there is not much ordinary people can do. About as many Republicans and leaners say ordinary citizens can influence the government in Washington (47%) as say there’s not much ordinary citizens can do (51%).

Among the 13% of the public that does not identify or lean toward either party – a group that is far less likely to be registered to vote – just 44% say voting gives people some say in how government runs things, while 49% say it doesn’t really affect how government runs things.

Seven-in-ten of those with a post-graduate degree (70%) and 65% of those with a college degree say voting gives people some say in government; somewhat smaller shares of those with only some college experience (58%) or those with no more than a high school diploma (51%) say the same.

Unlike views on voting, there are no educational differences in the shares saying ordinary people can influence government if they make the effort.

Blacks (58%) and Hispanics (57%) are more likely than whites (47%) to say that ordinary citizens can influence the government in Washington, if they’re willing to make the effort. There are no racial differences in views of the impact of voting.

These two measures of opinion on the impact of voting and on ordinary citizens’ ability to influence the government in Washington can be combined to create a scale of political efficacy. Those who rank “high” on the scale say both that voting gives people some say in how government runs things and that ordinary citizens can do a lot to influence the government in Washington, if they are willing to make the effort. “Medium” political efficacy includes those who hold only one of the two views, while “low” political efficacy describes those who do not hold either view.

Overall, 39% of the public falls into the high political efficacy category, while 33% have medium political efficacy and 28% have low political efficacy.

Political efficacy is higher among those with more education. For example, 47% of those with a post-graduate degree rank high on the scale of political efficacy, compared with 33% of those with no more than a high school diploma.

Across political groups, Democrats and leaners are somewhat more likely to have high political efficacy (44%) than Republicans and Republican leaners (36%)

And high political efficacy is somewhat more widespread among the politically engaged (registered voters who vote regularly and follow news about government) than among the less engaged (43% vs. 36%).

Having high political efficacy – the feeling that voting and individuals can influence government – is associated with more positive views of government across realms.

While trust in government is low across all groups, those with high political efficacy (27%) are more likely than those with medium (17%) or low (10%) levels of efficacy to say they trust the government to do what’s right always or most of the time.

Similarly, just 16% of those with high political efficacy are angry with government, compared with 22% of those with medium political efficacy and 30% of those with low levels of efficacy.

On other overall assessments of government, those with high political efficacy stand out for holding the least negative views. For example, among those with high political efficacy, as many say the government often does a better job than people give it credit for (48%) as say it is almost always wasteful and inefficient (48%). Among those with lower levels of political efficacy, more describe the government as almost always wasteful and inefficient (60% of those with medium political efficacy and 67% of those with low efficacy).

When it comes to the amount of reform the federal government needs, those with high levels of political efficacy (48%) are much less likely than those with medium (59%) or low (74%) efficacy to say the government is in need of very major reform. As many as 48% of those with high political efficacy say the federal government is basically sound and needs only some reform.

Levels of political efficacy also are tied to views of elected officials. While the public is broadly critical of elected officials on several key character traits, those with high levels of political efficacy hold the least-negative views. For example, those with high political efficacy are 19 percentage points more likely than those with low political efficacy to say that elected officials are honest; nonetheless, just 36% of those with high political efficacy say the term honest describes elected officials.

A similar pattern is evident within partisan groups: Among Republicans and Republican leaners, as well as Democrats and Democratic leaners, those with a higher sense of political efficacy tend to be less critical of government and elected officials, though in many cases views remain quite negative.

Public’s assessment of country’s problems, own ability to address them

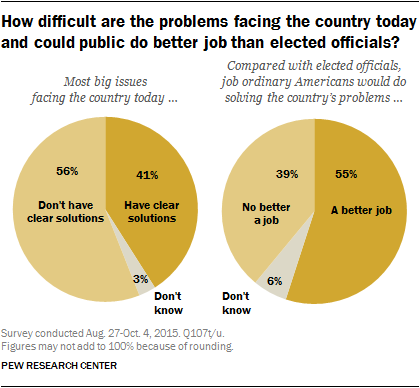

Amid high frustration with the government, most Americans see the challenges facing the country as difficult to solve, but most also say that ordinary Americans would do a better job solving the country’s problems than elected officials.

Overall, 56% say that most big issues facing the country today do not have clear solutions; 41% say there are clear solutions to most big issues facing the country today.

At the same time, 55% think that ordinary Americans would do a better job solving the country’s problems than elected officials, while 39% say they would do no better than those currently in elected office.

The public’s view that ordinary Americans would do a better job than elected officials likely reflects the low regard in which officials are held and is not entirely an endorsement of the public’s competency. A separate measure included in the survey finds that just 34% say they have either a very great deal or good deal of confidence in the wisdom of the American people when it comes to making political decisions, significantly lower than in 2007 (57%) and 1997 (64%).

Among the 41% of the public who say there are clear solutions to the big issues facing the country, fully 63% say they think ordinary Americans would do a better job than elected officials solving the country’s problems. By comparison, about half (49%) of those who say there are not clear solutions to the county’s problems think regular Americans could do a better job than elected officials.

Across most demographic and political groups, majorities reject the view that the country’s problems have easy solutions.

Just 38% of Democrats and leaners say there are clear solutions to most big issues; 60% say there are not. Republicans and leaners are somewhat more likely to see clear solutions (46% say there are, 52% say there are not).

Politically engaged Republicans are one of the few groups in which a majority says the country’s problems have clear solutions (56% vs. 43%). As a result, the partisan difference on this question is significantly larger among the politically engaged public (17 points, compared with 8 points overall).

By a 60%-36% margin, women say most big issues facing the country today do not have clear solutions. Among men, opinions are more divided: 51% say most issues do not have clear solutions, while 47% say they do.

There are only modest differences on this question across levels of educational attainment, with narrow majorities of all groups saying there are not clear solutions to the country’s top problems.

By nearly two-to-one, more Republicans and GOP leaners say that ordinary Americans would do a better job than elected officials solving the country’s problems (62%) than say ordinary people would not do a better job (32%). Democrats have less confidence that the public would have more success than politicians: 49% of Democrats and leaners say ordinary Americans would do better, while nearly as many (45%) say they would not.

The view that ordinary people could do a better job is particularly prevalent among politically engaged Republicans: Nearly seven-in-ten (68%) say this. Views among engaged Democrats and leaners on this question (48% better job) are little different from those of less-engaged Democrats.

Those with higher levels of education are more skeptical that ordinary Americans would do a better job solving the country’s problems than elected officials: Among those with a post-graduate degree, 45% say the public would do better than politicians, while 49% say they would not. Those with a college degree are slightly more likely to say ordinary Americans would do better than elected officials (50% vs. 44%). Clear majorities of those with only some college experience (55%-38%) and those with no more than a high school diploma (58%-36%) say ordinary Americans would do a better job solving the country’s problems than elected officials.

Among adults under age 30, about as many say ordinary Americans would do a better job than elected officials (49%) as say they would not (47%). Among those in older age cohorts, larger percentages say the public would do a better job solving problems than elected officials. For example, 62% of those ages 50-64 say this, compared with just 32% who say the public would not do better than elected officials.

While most think ordinary Americans would do a better job than elected officials, independent assessments of the public’s political wisdom are relatively negative, and have fallen in recent years.

While most think ordinary Americans would do a better job than elected officials, independent assessments of the public’s political wisdom are relatively negative, and have fallen in recent years.

Overall, just 34% say they generally have a very great deal or a good deal of confidence in the wisdom of the American people when it comes to making political decisions; a far greater share (63%) say they have not very much confidence or none at all. Confidence in the public’s political wisdom is down 23 points from 2007, when it stood at 57%. In 1997, nearly two-thirds (64%) said they had confidence in the public’s political wisdom.

There is no difference in views of the public’s political wisdom across party lines: Just 37% of Democrats and leaners and 36% of Republicans and leaners express at least a good deal of confidence. Similarly, the decline in confidence in the public’s ability to make political decisions over the past 18 years has occurred about equally among Republicans and Democrats.

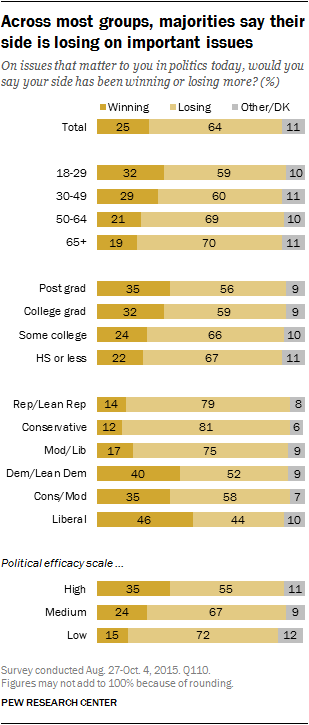

On important political issues, most see their side as ‘losing’

For many Americans, generally negative feelings toward government are accompanied by the view that on the important issues of the day their side has been losing more often than winning.

Overall, 64% say that on the issues that matter to them in politics today, their side has been losing more often than it’s been winning. Only a quarter (25%) say they feel their side has been winning more often than losing; 11% volunteer that their side has been winning as often as losing, that they don’t think about politics in this way, or that they don’t know.

The feeling that one’s side has been losing on the issues is widespread across demographic and political groups. In fact, clear majorities of nearly all groups – with the exception of liberal Democrats and leaners – say they feel like their side has been losing more than winning.

About eight-in-ten Republicans and Republican leaners (79%) say they feel their side has been losing on the important political issues, while just 14% feel they’ve been winning. Comparably large majorities of conservative (81%) and moderate and liberal (75%) Republicans feel their side has been losing more than winning.

Among all Democrats and Democratic leaners, views are more mixed: 52% say their side has been losing more than winning on important political issues, while 40% say they’ve been winning more often. Among Democrats, there is a significant divide in views across ideological lines. By a 58%-35% margin, more conservative and moderate Democrats say their side has been losing more than winning on the issues that matter to them. Liberal Democrats are as likely to say their side has been winning (46%) as losing (44%) more often. This mixed rating among liberal Democrats is the most positive view of any group in the survey.

Across levels of educational attainment, the view that one’s side has been losing more often than winning is particularly widespread among those with no more than a high school diploma (67%) and those with only some college experience (66%). Somewhat smaller majorities of college graduates (59%) and post graduates (56%) also say their side has been losing more often than winning on important issues.

Views on winning and losing in politics are tied to overall feelings toward government. Among the share who say their side has been winning on issues more often than losing, more say they are content with the federal government (34%) than say they are angry (9%), while 55% say they are frustrated. Among those who say their side has been losing more often than winning, a greater share is angry with government (27%) than content (9%), while 61% say they are frustrated.

Views on winning and losing in politics are tied to overall feelings toward government. Among the share who say their side has been winning on issues more often than losing, more say they are content with the federal government (34%) than say they are angry (9%), while 55% say they are frustrated. Among those who say their side has been losing more often than winning, a greater share is angry with government (27%) than content (9%), while 61% say they are frustrated.

Most say politics not a struggle between right and wrong

Although there has been a marked rise in partisan antipathy – the dislike of the opposing party – in recent years, most Americans do not go so far as to say they view politics as a struggle between right and wrong.

Overall, while 44% say they think about politics as a struggle between right and wrong, 54% say they do not see politics this way.

The view that politics is a struggle between right and wrong is more common among blacks (57%) than among Hispanics (47%) or whites (40%).

Those with higher levels of educational attainment are particularly unlikely to see politics in these stark terms: Just 30% of those with post-graduate degrees and 34% of those with college degrees, say politics is a struggle between right and wrong. By comparison, 51% of those with no more than a high school diploma and 44% of those with some college experience say this.

Conservative Republicans and leaners are more likely than those in other partisan groups to say they view politics as a struggle between right and wrong: 53% say this, compared with just 38% of moderate and liberal Republicans, 45% of conservative and moderate Democrats, and 37% of liberal Democrats.

Interactive

Interactive