There is nothing new about Republicans disliking the Democratic Party or, conversely, Democrats not liking the GOP. But the level of antipathy that members of each party feel toward the opposing party has surged over the past two decades. Not only do greater numbers of those in both parties have negative views of the other side, those negative views are increasingly intense. And today, many go so far as to say that the opposing party’s policies threaten the nation’s well-being.

Though negative ratings of the other party were common 20 years ago, relatively few Republicans and Democrats had deeply negative opinions. In 1994, when the GOP captured the House and Senate after a bitter midterm campaign, about two-thirds (68%) of Republicans and Republican leaners had an unfavorable opinion of the Democratic Party, but just 17% had a very unfavorable opinion. At the same time, though a majority of Democrats and Democratic leaners (57%) viewed the GOP unfavorably, just 16% had a very unfavorable view. Today, negative ratings have risen overall (about eight-in-ten of both Republicans and Democrats rate the other party unfavorably), but deeply negative views have more than doubled: 38% of Democrats and 43% of Republicans now view the opposite party in strongly negative terms. The rise in negative views of the opposing party is also seen in “feeling thermometer” ratings in the American National Election Studies, as partisans now give “cooler” ratings to the opposing party than they did in the past.

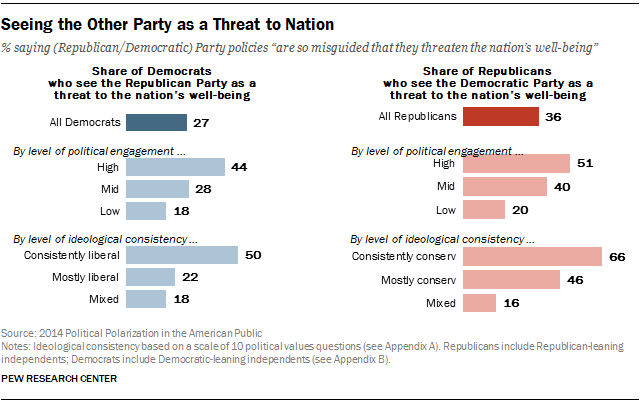

The survey finds that this strong dislike verges on alarm for many. In both political parties, most of those who view the other party very unfavorably say that the other side’s policies “are so misguided that they threaten the nation’s well-being.” Overall, 36% of Republicans and Republican leaners say that Democratic policies threaten the nation, while 27% of Democrats and Democratic leaners view GOP policies in equally stark terms.

This kind of hostility toward the opposing party is strongly related to political participation and activism. For example, 54% of Republicans and 46% of Democrats who have made campaign donations in the past two years describe the other political party as a threat to the nation. In other words, those who arguably have the greatest impact on politics are most likely to have strongly negative feelings toward the opposing party.

And among members of both parties, intense dislike of the political opposition – like ideological polarization – is strongly linked to other views and behaviors as well, such as how willing people are to support compromise in Washington, and how they view personal interactions with people from the other political party.

The growing partisan antipathy detailed here is one major aspect of political polarization. Another is ideological polarization – the growing share of Americans who hold consistently liberal or conservative views across a wide range of issues. These trends are connected, but not identical, and both ideological consistency and partisan antipathy individually are important elements of the broader polarized landscape.

Ideology and Partisan Antipathy Increasingly Intertwined

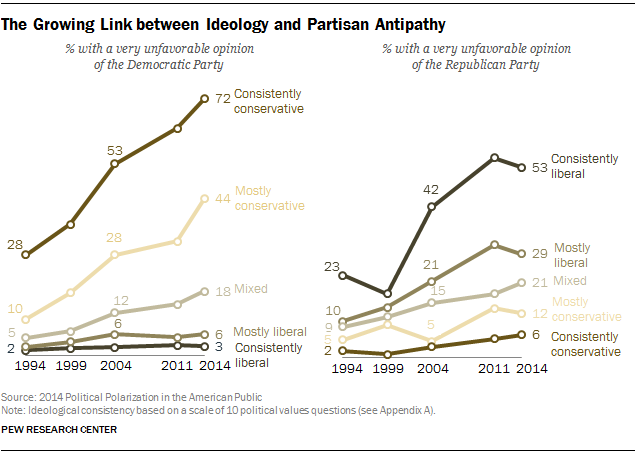

Twenty years ago, fewer Americans were consistently liberal or conservative in their views about politics and society and even those who were ideologically oriented did not express the animosity toward the other side that is common today. In 1994 – hardly a moment of goodwill and compromise in American politics – just 23% of consistent liberals expressed a very unfavorable view of the Republican Party. And just 28% of consistent conservatives saw the Democratic Party in equally negative terms.

But today, the majority of ideologically-oriented Americans hold deeply negative views of the other side. This is particularly true on the right, as 72% of consistent conservatives have a very unfavorable opinion of the Democratic Party. Consistent liberals do not feel as negatively toward the GOP; nonetheless, 53% of consistent liberals have very unfavorable impressions of the GOP, more than double the share that did so two decades ago.

A Deep-Seated Dislike, Bordering on Sense of Alarm

At a time of historically low levels of trust in government and other national institutions, expressing a “very unfavorable” opinion of the opposing political party may not seem like a signal of intense hostility. However, when given the chance to express even stronger criticism, most who hold highly negative views of the opposing party do so.

After expressing a very unfavorable view of one or the other party, respondents were asked: “Would you say the party’s policies are so misguided that they threaten the nation’s well-being, or wouldn’t you go that far?” The question was intentionally designed to suggest that this was a high bar; nevertheless, the vast majority of those who were asked the question agreed. Among all Democrats and Democratic leaners, 27% go so far as to say the GOP is a threat to the well-being of the country. Among all Republicans and Republican leaners, more than a third (36%) say Democratic policies threaten the nation.

Republican Antipathy toward Obama

While there are plenty on both the left and the right who express these levels of antipathy toward the other side, there is substantially more anger among conservatives than among liberals. At the most extreme, two-thirds (66%) of consistently conservative Republicans see the Democratic Party as a threat to the nation’s well-being, compared with the half (50%) of consistently liberal Democrats who say the same about the Republican Party. And this concern reaches well beyond the right wing of the Republican Party, as nearly half (46%) of mostly conservative Republicans see the Democratic Party as a threat to the nation’s well-being; by contrast, 22% of mostly liberal Democrats see the GOP as a threat.

At least in part, the strongly negative views Republicans have of the Democratic Party reflect their deep-seated dislike of Barack Obama. In the current survey, just 12% of Republicans and Republican leaners say they approve of the job Obama is doing in office, while 84% disapprove, including 71% who very strongly disapprove.

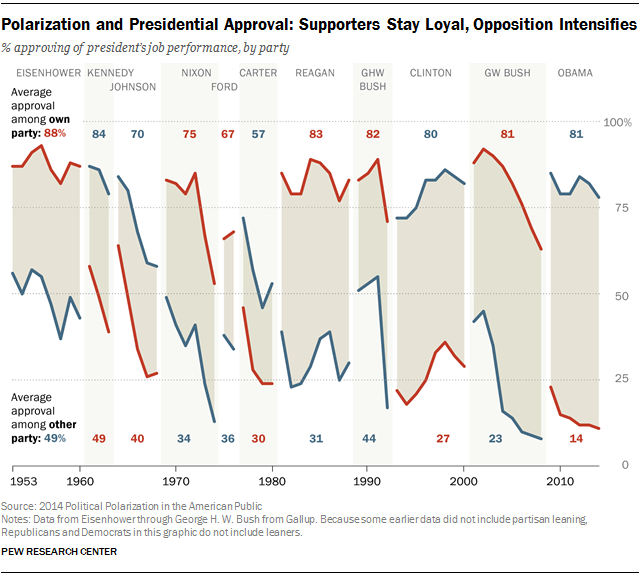

This impassioned Republican discontent has persisted from the early days of Obama’s presidency, yet it is only the latest instance of a longer pattern in how the public assesses its presidents. There has been a steadily growing level of partisan division over presidential performance over the past 60 years, and it is driven almost entirely by broader disapproval from the opposition party, not by greater loyalty among the president’s party. And in that regard, the phenomenon is not limited to Republicans. At a comparable point in George W. Bush’s presidency eight years ago, Democratic disapproval of Bush’s job performance was on par with Republicans’ ratings of Obama today; in April 2006, 87% of Democrats and Democratic leaners disapproved of Bush’s job performance, and 75% very strongly disapproved.

Modern presidents, from Dwight Eisenhower through Barack Obama, have generally enjoyed a job approval rating of around 80% from their own partisan base. The exceptions are the lower ratings Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford and George W. Bush received from within their parties in their difficult final years in office, and the distinct lack of enthusiasm Democrats expressed for Jimmy Carter through most his presidency. Obama’s job approval rating among Democrats (on average, 81% approval over the course of his presidency so far) has been roughly the same as Republicans’ ratings for two of the party’s icons – Ronald Reagan in the 1980s and (83%) and Eisenhower in the 1950s (88%).

By comparison, the views of people in the opposing party have become steadily more negative. From 1953-1960, an average of nearly half (49%) of Democrats said they approved of the job Republican president Dwight Eisenhower was doing in office. Over the course of Reagan’s presidency, nearly a third (31%) of Democrats approved of his job performance. Just over a quarter (27%) of Republicans offered a positive assessment of Bill Clinton between 1993 and 2000. But the two most recent presidents have not received even this minimal support. George W. Bush’s job ratings among Democrats were relatively strong in the post-9/11 period, but in the last five years of his presidency, only 12% of Democrats, on average, approved of his job performance. That is similar to Obama’s ratings among Republicans (14% on average) over the course of his presidency.

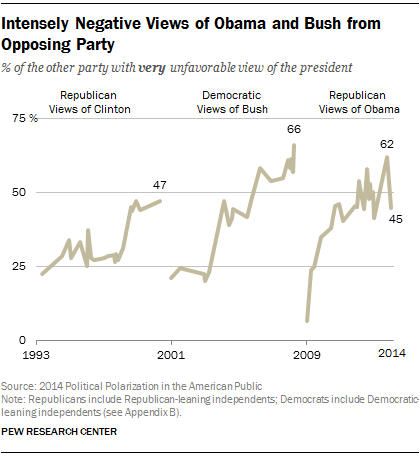

Not only have partisans become more uniform in their disapproval of presidents from the other party, they are also more inclined to express deeply negative personal evaluations of the men holding the office. Most Republicans (78%) have an unfavorable opinion of Obama, and 45% rate him very unfavorably. Those ratings represent an improvement in GOP views of Obama. In the midst of the government shutdown and debt limit negotiations last October, 88% viewed him unfavorably, with 62% saying their opinion was very unfavorable.

But this is not unique to Republican views of Obama. Democratic views of George W. Bush reached similar territory during his second term, as the war in Iraq became a partisan dividing line compounded by reactions to other aspects of Bush’s presidency, including his handling of Hurricane Katrina. By April 2008, nearly nine-in-ten Democrats had unfavorable views of Bush – 66% viewed him very unfavorably.

By contrast, this level of deeply negative personal evaluations from the opposing side wasn’t as evident during Bill Clinton’s presidency. Even as clear majorities of Republicans expressed unfavorable opinions of Bill Clinton during his time in office, the proportion saying their opinion was very unfavorable peaked at 47%.

Antipathy and Engagement

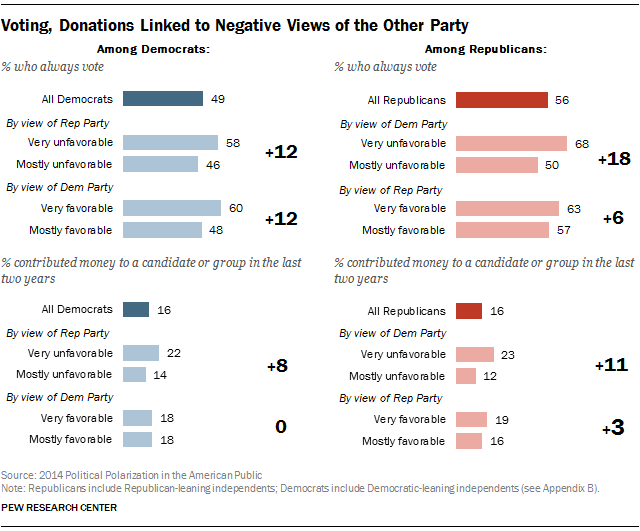

Holding deeply negative views of the opposite party and its leaders is correlated with political participation, and this is particularly true among Republicans in the current context. Republicans who hold a very unfavorable opinion of the Democratic Party are 18 points more likely than those whose opinion is mostly unfavorable to say they always vote. They are also almost twice as likely to have made a donation to a campaign or candidate (23% vs. 12%). Importantly, how Republicans view their own political party has little association with their participation in these ways. Those who hold very favorable views of the GOP are no more or less likely to be politically active than those with less favorable views.

The same pattern exists when it comes to Democratic campaign donors. Democrats with a very unfavorable opinion of the GOP are substantially more likely than those who feel only mostly unfavorably to have made a donation in the past two years (22% vs. 14%). But there are no differences in self-reported donations among Democrats who have a very favorable opinion of their own party and those who have a mostly favorable view. Yet when it comes to voting among Democrats, strong views of both political parties tend to matter. Democrats who view the GOP very unfavorably are 12 points more likely to always vote than those who only mostly dislike the Republican Party. But those who feel very positively about their own party are also 12 points more likely to always vote than those who are only mostly positive.

As we show elsewhere, both partisan animosity and ideological consistency are linked to higher levels of political participation, and in fact the effect is compounded among those who think both in ideological and partisan terms. And both also affect how Americans view negotiations and compromise in Washington and even how people interact with those around them. As partisan antipathy and ideological consistency have grown, each contributes substantially to a more polarized political environment in elections, in Washington and in society more generally.