The issue of the debt and the deficit – and what to do about it – has paralyzed Washington lawmakers. But when it comes to measures for reducing the deficit on which they might reach common ground, they will get little help in building support for an agreement by turning to public opinion.

In my years of polling, there has never been an issue such as the deficit on which there has been such a consensus among the public about its importance – and such a lack of agreement about acceptable solutions.

When the public was asked in March to volunteer the most important problem facing the nation, only unemployment and the economy were cited more often.

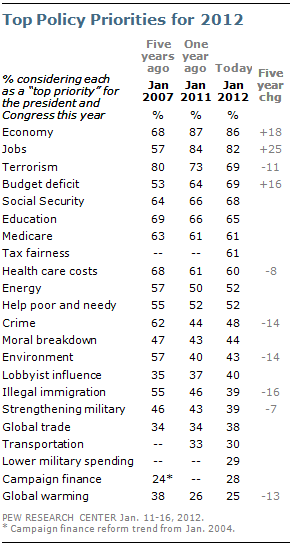

The deficit has also risen in importance in the public mind when Americans are asked at the beginning of each year what they believe to be the top national priorities for the president and the Congress.

The Pew Research Center began measuring national priorities in 1997. Jobs, education, Social Security, Medicare and the budget deficit were at the top of the list then just as they are now, in 2012.

The deficit had earlier slipped as a priority during the last years of the Clinton administration when the budget was in surplus and following the 9/11 attacks when terrorism rose as a priority.

Today, however, the budget deficit stands out as one of the fastest growing priorities for Americans, rising 16 percentage points since 2007 and ranking third with 69% calling it a top priority. Only the economy and jobs, ranking first and second at 86% and 82% respectively, have registered bigger increases over this period – hardly surprising, given the financial meltdown that began in 2008 and whose impact is still being felt today.

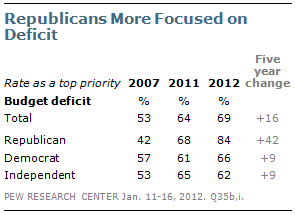

While an increasing number of Americans share concern about the deficit, the issue has often been one that generates intense reactions among Republicans given their traditional preference for a smaller and less activist federal government.

The number of Republicans ranking the budget deficit as a top priority has spiked to 84% compared to 68% a year ago, and 42% five years ago. Concern has also risen among Democrats and independents, but nowhere near to the degree it has among Republicans. About two-thirds (66%) of Democrats rank the deficit as a top priority compared to 61% last year and 57% in 2007. Just over six-in-ten (62%) of independents say the deficit is a top priority, compared to 65% a year ago and 53% in 2007.

The Republican emphasis on the deficit is reflected in the voting priorities of those who favor presumptive Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney and those who support President Obama.

Voters who rank the federal budget deficit as a top priority favor Romney over Obama by a 52% to 42% margin.

Concerns over the debt has become a troubling issue on both sides of the Atlantic. However, the politics surrounding it differs in the U.S. A median 81% of the publics in European countries regard the size of the national debt as a major threat to economic well-being; 71% of Americans share that view.

But the unease over the national debt is far more likely to be a partisan issue in the U.S. than it is in Europe. Europeans, whatever their political leanings, tend to see indebtedness the same way. The left-right divide in concern is five percentage points in Germany, four in France, and three in Britain. It is 20 points in the United States, with only 59% of liberals ranking debt as a major threat to the economy compared with 79% of conservatives.

While there is a clear and broad consensus in the U.S. about the importance of dealing with debt and deficit, that is where the clarity and consensus stops – undermined by the disconnect

between the public’s stated desire for a smaller government delivering fewer services, and its resistance to spending cuts and, in other cases, tax increases.

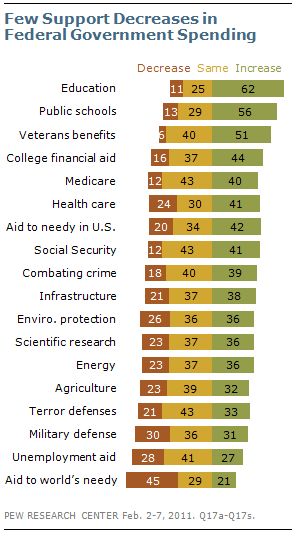

By a margin of 52% to 39%, the largest in five years, Americans express a preference for smaller government as opposed to a larger government providing more services.

But even given that preference, there was not a great deal of support for decreases in spending across a range of issues in a February 2011 survey.

The survey did find that fewer Americans supported spending increases than in previous years, but even with those declines, the number of Americans favoring increases still outnumbered those favoring decreases on 15 of 18 issues tested. In addition, a substantial number are willing to see spending held steady.

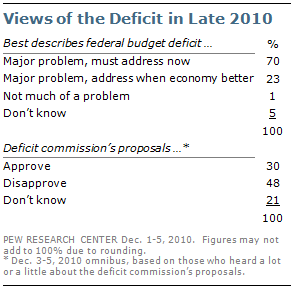

The reluctance to cut spending, or support tax increases, was foreshadowed by reaction to the sweeping recommendations issued in December 2010 by the Simpson-Bowles deficit commission created by President Obama. The commission had called for deep cuts in military and domestic spending, reducing or ending popular tax breaks (including the home mortgage interest deduction) and changes to entitlement programs.

While 70% of Americans said at the time that the budget deficit was a major problem that needed to be addressed immediately, they disapproved of the commission’s proposals by a 48% to 30% margin, with 21% expressing no opinion.

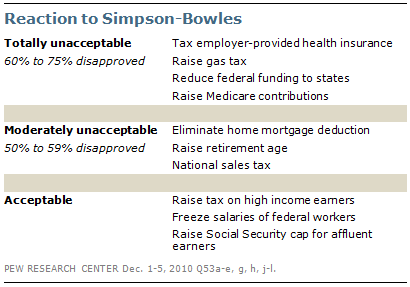

When it came to specifics, the public had three kinds of reactions:

About two-thirds or more said “no” to proposals for taxing employer-provided health insurance plans, raising the gasoline tax, reducing federal funding to states and raising the contributions the Medicare recipients pay into the program.

Proposals drawing more moderate opposition – ranging from 52% to 58% – would eliminate the home mortgage interest deduction, raise the Social Security retirement age, and impose a national sales tax.

What the public saw as acceptable included raising the Social Security contribution cap for affluent recipients (64% in favor) and freezing the salaries of federal workers (59% in favor). At the same time, a plurality backed raising taxes on high-income earners by not including them in an extension of the Bush-era tax cuts, (47% favored making the cuts available only for those earning less than $250,000 a year, compared to 33% who supported an extension for all).

Many of those findings were echoed in a later May 2011 survey conducted in the run-up to last summer’s fractious debt ceiling debate.

Majorities ranging from 54% to 59% rejected proposals to reduce funding to help lower-income Americans, reducing Social Security benefits for high-income seniors, and raising the Social Security retirement age. More than seven-in-ten opposed reducing funding to states for roads and education, and taxing employer-provided health insurance. The public was divided on limiting the home mortgage deduction interest and cutting agriculture subsidies.

The areas where there was support for cuts included reducing foreign aid (a relatively small part of the budget), raising the Social Security contribution cap, taxing those with annual incomes of over $250,000, limiting tax deductions for large corporations and reducing military commitments overseas.

The most heated and politically-charged issue when it comes to proposals to deal with the debt/deficit debate is what, if anything, to do about entitlement programs.

The public overwhelmingly regards Social Security as a program that has been good for the country, with 87% holding that view. More than three-quarters (77%) also share the concern that its financial condition is only fair or poor. But that’s where the consensus ends.

There is strong resistance to any cuts in entitlement programs in order to reduce the deficit, with 58% of Americans saying that to maintaining benefits as they are trumps deficit reduction, (35% favor taking steps to reduce the deficit). Nearly six-in-ten (59%) put a higher priority on avoiding any future cuts in benefit amounts than on avoiding Social Security tax increases for workers and employers, with 32% believing that avoiding tax increases is more important.

Agreement that Social Security benefits should be maintained at current levels even if it removes one way to cut the deficit is shared among all age groups. But beyond that consensus, there are generational divides on a host of issues.

The importance of keeping benefits at current levels is felt more intensely by Baby Boomers and the over-65 Silent generation than it is among Millennials, (62% of Boomers and 64% of Silents want to keep benefits untouched compared to 53% of Millennials). Six-in-ten or more of Gen Xers, Baby Boomers, and Silents want to avoid any future cuts in Social Security benefit amounts, far outnumbering those in their age groups who put the priority on avoiding any Social Security tax increases. Far fewer Millennials (49%) say they want to avoid any future benefit cuts, and more of them (44%) say their priority is to avoid tax increases.

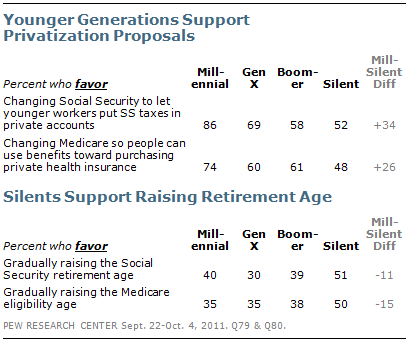

There are also generational divides on proposals that would privatize Social Security and gradually raise the age of eligibility, both of which get a decidedly mixed reaction from those now of retirement age or older.

Fully 86% of Millennials favor changing Social Security to let younger workers invest Social Security taxes in private accounts. Support for that proposal is lower among Gen Xers (69%), Boomers (58%) and Silents (52%). The age divide extends to the idea of changing Medicare so people can use their benefits towards purchasing private health insurance. About three-quarters of Millennials (74%) favor this proposal, compared to 48% of Silents.

When it comes to the proposal to gradually raise the Social Security retirement age, the Silents are at odds with the younger generations. About half (51%) of Silents support this idea, compared to 39% of Boomers, 30% of Gen Xers and 40% of Millennials.

In addition to generational differences, there are sharp partisan disagreements.

About two-thirds (67%) of Democrats oppose future cuts in Social Security compared to 49% of Republicans. On Medicare, 41% of Republicans say its recipients should pay more of their health care costs compared to 23% of Democrats. More than seven-in-ten (72%) Democrats say recipients already pay enough compared to 53% of Republicans.

While the public is resistant to a wide range of proposals to deal with the deficit, it has expressed a solid distaste for the deadlock in Washington.

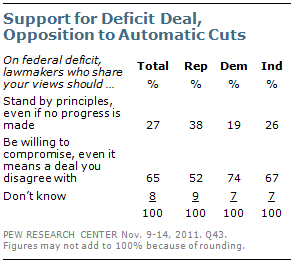

In late 2011, about two-thirds (65%) wanted their lawmakers to be willing to compromise rather than stand by their principles, even if standing by principles meant no progress was made. That view was held by 74% of Democrats and 67% of independents compared to 52% of Republicans.

The public did signal its flexibility on strategy for dealing with deficits, with a majority favoring a combination of major program cuts and tax increases as part of any agreement. Just 17% said the best approach was using only major spending cuts and just 8% said deficit reduction should be achieved through only tax increases. Democrats were the most likely to favor the combination approach, with 71% holding that view compared to 53% of Republicans. Independents were in between at 63%.

The fact that the parties, in the end, did not break their deadlock exacted a political cost. The debt ceiling fight in the summer of 2011 resulted in the public holding less favorable views of President Obama and House Speaker John Boehner.

Both parties lost ground in public esteem, but the Republicans suffered the biggest setbacks. Americans associated the Republicans with extreme positions while viewing the Democrats as the party of compromise, which is what the public wanted lawmakers to do as the prospect loomed of a federal government default. Opinion of the Republican leadership nose-dived over that summer. At the end of July, 42% of Americans saw Republicans in Congress less favorably after the weeks of debt negotiations, (44% said their opinions were unchanged and 11 percent said their opinion was more favorable). More generally, the Republican Party’s favorable rating sank to 34% in August 2011 compared to 42% in February, unfavorable views of the GOP rose from 51% to 59%. Democrats continued to get mixed marks, with 43% seeing them favorably and 50% unfavorably (compared to 48% favorable and 45% unfavorable in February).

The high level of disappointment and frustration reflected by this public reaction poses a serious conundrum for those in Washington wrestling with the debt and deficit issue – they are dealing with a public that is demanding solution to a problem which it has declared to be a major priority, but at the same time Americans are resistant, or divided at best, on the sacrifices that would be required to achieve a solution.

The bottom line appears to be that if the deficit and related entitlement programs are to be addressed, it may well have to be in spite of public opinion, not in response to it.