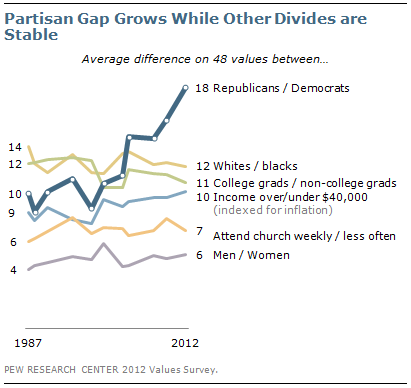

Even as party divisions over values have expanded over the last quarter century, gaps between other groups have remained relatively unchanged. Across the 48 values items tracked

regularly since 1987, average gender, age, race, education, income and religiosity differences have remained remarkably stable. Several of these demographic characteristics are associated with significant differences in values, but none have shown substantial change over time.

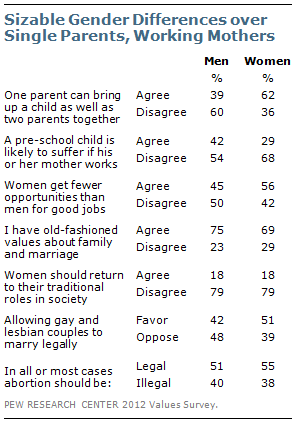

Of particular note is the size of the overall gender gap, which is modest. On average, men and women differ by only six points across these values questions. The size of the gender gap varies on different questions, but it remains relatively narrow across-the-board.

Differences between blacks and whites, college graduates and non-college graduates, high and low-income people and younger and older people are more substantial, although in each case these divisions are now dwarfed by partisan differences.

Age Differences in Social and Political Values

There have long been age divides in political and social values. Younger people tend to be less politically engaged, less religious, and more positive about government and what it can do.

As discussed in detail in a previous report on generational politics (See “The Generation Gap and the 2012 Election”, Nov. 3, 2011), much of the current political dynamic is a result of strong generational characteristics of the Millennial generation compared with Gen X, Baby Boomers and the Silent generation. There have been particularly wide differences in the voting patterns of younger and older Americans in the past few elections because of the contrast between a younger, more Democratically-oriented generation and an older generation that has consistently been more supportive of Republican candidates.

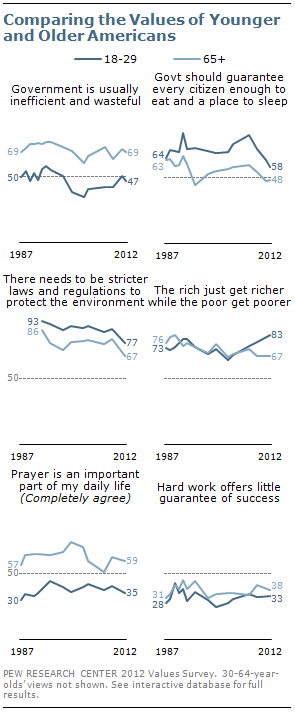

Many of the age differences over values have remained fairly constant over the past quarter century. In 1987, 18-to-29 year olds were considerably less skeptical than those 65 and older about the government’s ability to operate efficiently; that gap has endured ever since. Younger adults also have been consistently more supportive of the social safety net and of environmental policies, and they are significantly less religious.

One emerging age gap is over wealth disparities – 83% of those younger than 30 say it is really true that the rich just get richer while the poor get poorer, compared with 67% of those 65 and older.

But this does not mean there is an age divide over opportunity in America. Only a minority of younger and older Americans alike agree with the notion that hard work offers little guarantee of success. Similarly, fewer than half in any age group believes that success is determined by forces outside their control.

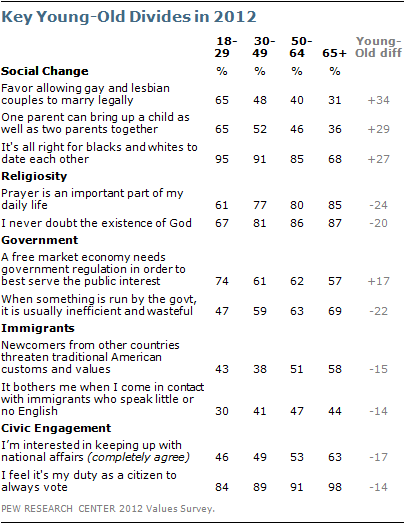

Not surprisingly, the largest gaps between younger (18-to-29) and older (65+) Americans in core values concern issues related to social change such as homosexual rights, single parenting, and racial integration.

Just 36% of those 65 and older say they agree with the statement that “One parent can bring up a child as well as two parents together,” compared with 65% of those younger than 30.

While sizable majorities of those in all groups approve of interracial dating, this sentiment is nearly universal among young people (95% agree). About two-thirds (68%) of those 65 and older agree. In terms of current political issues, there is more support for gay marriage among younger people, though support has grown across all age groups.

Some of these age gaps are related to a trend toward secularization in the younger age groups. Notably, people younger than 30 are substantially less likely than older people to say prayer is an important part of their lives (24-point gap). Research on generational patterns shows that this is not merely a lifecycle effect; the Millennial generation is far less religious than were other preceding generations when they were the same age years ago. (See graphic entitled “Rise of Religiously Unaffiliated among Younger Generations”, Nov. 3, 2011.)

Younger people also are less critical of government performance. While 69% of those 65 and older agree that “when something is run by the government, it is usually inefficient and wasteful,” this compares with only about half (47%) of those younger than 30. Related to this, younger people are more supportive of the government’s role in regulating the economy and providing a social safety net.

And younger people express far less negative attitudes about immigrants and the effects of immigration on the country. To be sure, the younger generations are far more ethnically diverse – the latest data suggest that one-in-five U.S. adults younger than 30 are of Hispanic background. But age differences in views of immigrants and immigration are not attributable to demographics alone. The gap in the views of younger and older whites is just as large.

Gender Gaps Modest Overall

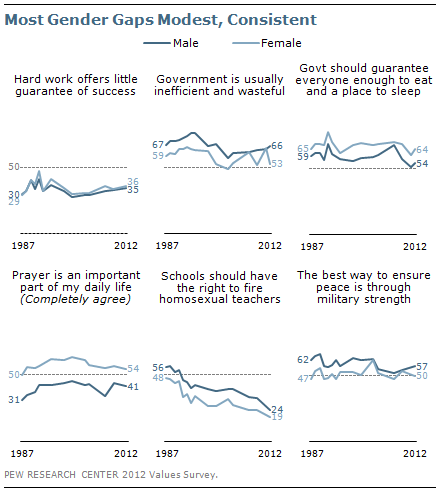

Although differences between men and women are evident across many values items, the size of these differences is generally modest, and on many items there is no significant difference at all. Moreover, what gender differences exist have neither increased nor decreased over time.

One of the larger value differences between men and women is in how religiously committed they are. Women are significantly more likely than men to say prayer is an important part of their lives, and to say they never doubt the existence of God. These gender gaps persist among both younger and older generations of men and women, as well as among college graduates and the less educated.

Despite their higher religiosity, women have not been more conservative th

an men on social issues. Women are about as likely as men to say that they have “old-fashioned values about family and marriage.” And on one of the most divisive social issues – homosexuality – women have tended to be more supportive of gay rights than men.

When it comes to government, men have generally been more skeptical of the government’s ability to act efficiently, and less supportive of the social safety net.

There is a substantial gender gap in attitudes about single parenting: About six-in-ten (62%) women say one parent can bring a child up as well as two parents together; only 39% of men share that view. Additionally, women are less likely than men to agree that “a pre-school child is likely to suffer if his or her mother works” (29% of women vs. 42% of men).

Whites and Blacks Differ Over Role of Government

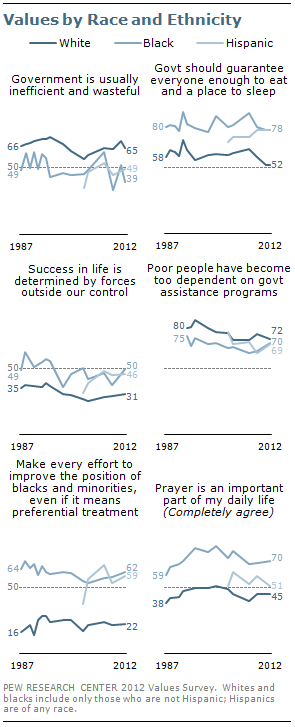

The differences in the views and beliefs of blacks and whites today are largely the same as when this project began in 1987. African Americans have consistently been more confident than whites in government’s ability to perform efficiently and more supportive of the social safety net and a larger role for the government in society.

Most notably, 62% of blacks say “we should make every possible effort to improve the position of blacks and other minorities, even if it means giving them preferential treatment.” Just 22% of whites agree. Twenty-five years ago, the gap was almost identical, 64% vs. 16%.

When it comes to the social safety net, 78% of blacks today say “the government should guarantee every citizen enough to eat and a place to sleep.” That figure was 80% in 1987. Among whites, 52% agree with this statement today, down slightly from 58% in 1987.

One of the defining values gaps between blacks and whites is over opportunity. Currently, half of blacks say “success in life is determined by forces outside our control,” compared with 31% of whites. Again, these figures are little changed from 25 years ago (49% of blacks, 35% of whites.)

While blacks overwhelmingly support a government safety net, they mostly agree with whites that poor people have become too dependent on government assistance programs. Currently, 72% of whites and 70% of blacks hold this view. While historically whites have been more likely to feel this way than blacks, the gap has been small relative to other divides over government and opportunity.

Religiosity remains a substantial racial gap. On all measures of religious intensity – the importance of prayer never doubting the existence of God and believing there will be a Judgment Day – the share of African Americans who not only agree, but completely agree, is far higher than among whites.

This religious conviction does not always mean blacks are more conservative on social issues, however. African American support for gay marriage has grown in recent years, but is still below support among whites (39% of blacks and 47% of whites now favor allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally). (See “Changing Views of Gay Marriage: A Deeper Analysis,” May 23, 2012.)

But there is no difference in the share of blacks and whites who say schools should have the right to fire gay teachers (24% of blacks, 20% of whites). Roughly equal majorities of blacks (69%) and whites (72%) say they have “old fashioned values about family and marriage,” though blacks are more likely than whites (28% vs. 14%) to say that “women should return to their traditional roles in society.”

Education and Income Gaps

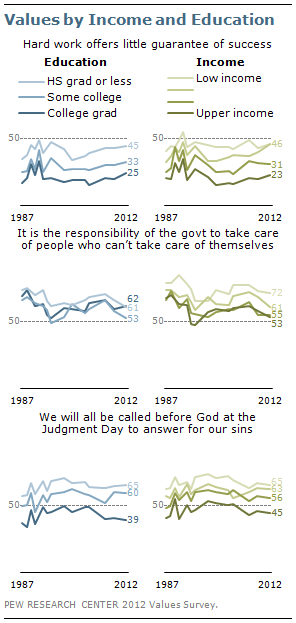

As has consistently been the case over the last quarter century, there are clear values divides by socioeconomic status. Apart from differences in financial security, some of the largest education and income gaps concern social issues and religiosity: Just 39% of college graduates believe we will all be called before God at the Judgment Day to answer for our sins, compared with 60% who did not finish bachelors’ degrees and 65% of those who never attended college. Low- and high-income people differ by similar degrees. These divides have been consistent over the past 25 years.

Large income and education divides also have been steady when it comes to questions of personal efficacy: Nearly half of those in the bottom two income quartiles say “hard work offers little guarantee of success,” compared with just 23% of those in the top income quartile. Those with no more than a high school diploma are also far more likely to believe this (45%) than are those with a college degree (25%). Those in lower income and education categories also are the most likely to say that “the rich just get richer while the poor get poorer.”

Income and education gaps are not always parallel. Lower-income Americans always have been more supportive of the social safety net than those in higher income brackets. There is not as much variation across educational lines. In fact, in the current survey, college graduates and those who never attended college have that same view on whether the government has a responsibility to take care of people who can’t take care of themselves.